GOBELINS TAPESTRIES MANUFACTORY (Woven 1687 – 1688)

After designs by ALBERT ECKHOUT (Groningen, ca. 1610 – 1666)

and FRANS POST (Haarlem, 1612 – 1680)

First edition of the Anciennes Indes series

The Kongolese Dignitary carried by Two Porters

(“Le roi porté par deux Maures”)

Wool and silk weft

15 feet 4 inches x 10 feet 8 inches

(approx. 467 x 325 cm)

Woven basse lisse, within the ‘first’ four-sided gold and red acanthus borders on a blue ground, with narrow inner husk and outer red and gold banded borders, with blue outer selvedge

The Mapuche Lancer on Horseback (“L’Indien à Cheval) or The Dappled Horse (“Le Cheval pommelé”)

Wool and silk weft

15 feet 1 inch x 11 feet 3 inches

(approx. 458 x 344 cm)

Woven basse lisse, within the ‘first’ four-sided borders of gold and red alternating acanthus leaf and guilloche bands on a blue ground, with further narrow inner husk and outer red and gold banded borders, with blue outer selvedge

Inscribed on the reverse: No 158. INDIENS./ 8.P.4. au,/ 3 au[i]

Provenance:

Produced in the Manufacture Royale des Gobelins, Paris, 1687–1688 for King Louis XIV of France.

Delivered to the Garde-Meuble de la Couronne, 14 June 1689.

Transferred to the Louvre, Paris, 5 August 1793.

Passed into private ownership at an unknown date following the French Revolution.

Charles-Henri Braquenié, Paris; his sale, Paris, 18 May 1897, lots 3 and 4

Don Carlos de Beistegui, Palazzo Labia, Venice; sold 6–10 April 1964, lots 577 b and c; where acquired by:

Private Collection

Alberto Bruni Tedeschi Collection, Castle of Castagneto Po, near Turin; his estate sale, Sotheby’s, London, 21 March 2007, lots 111 and 113; where acquired by:

W. Graham Arader III, New York (2007-present)

Literature:

Jules Guiffrey, Inventaire general du Mobilier de la Couronne sous Louis XIV (1663–1715), vol. 1, Paris, 1885–1886, p. 360.

Maurice Fenaille, État general des tapisseries de la Manufacture des Gobelins depuis son origine jusqu'à nos jours, 1600–1900, vol. 2, “Période de la foundation de la Manufacture Royale des Meubles de la Couronne sous Louis XIV, en 1662, jusqu’en 1699, date de la réoverture des ateliers,” Paris, 1903, pp. 376-378, 394-395, 397.

P.J.P. Whitehead and M. Boeseman, A Portrait of Dutch 17th Century Brazil: Animals, Plants and People by the Artists of Johan Maurits of Nassau, New York, 1989, pp. 119-120.

Charissa Bremer-David, French Tapestries & Textiles in the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 1997, p. 15.

Nello Forti Grazzini, “The Striped Horse,” in Tapestry in the Baroque. Threads of Splendor, ed. Thomas B. Campbell, exhibition catalogue, New York, 2008, p. 393.

Jean Vittet and Arnauld Brejon de Lavergnée, La collection de tapisseries de Louis XIV, Dijon, 2010, p. 394.

Gerlinde Klatte, in Exotismus und Globalisierung: Brasilien auf Wandteppichen: die Tenture des Indes, eds. Gerlinde Klatte, Helga Prüßmann-Zemper, and Katharina Schmidt-Loske, Berlin, 2016, pp. 348, 355.

Victoria Ramírez Ruiz, “Los Tapices de Las Indias en las Colecciones de la Nobleza,” in De Flandres a Extremadura: Humanismo y Naturaleza en los Tapices de Badajoz, Badajoz, 2019, pp. 381, 391-392.

Carrie Anderson, “The Old Indies at the French Court: Johan Maurits’s Gift,” Early Modern Low Countries, vol. 3, no. 1 (2019), pp. 36.

Ernst van den Boogaart, Het land van de suikermolen: Johan Maurits' Brazilië, Zwolle, 2021, pp. 97, 107-111.

The eight monumental tapestries that constitute the Anciennes Indes series are not only masterpieces in their own right, but also significant milestones in the history of European visual exploration and the representation of people beyond the European continent. As Dr. Nello Forti Grazzini has written, each depicts a “vivid, living, dynamic tableau vivant in which native people with their specific costumes and objects, animals and plants never before seen by most Europeans…form imposing images of tropical scenery, intended to be a true ethnographic, zoological, and botanical report of North-Eastern Brazil as it was in the 17th century.”[ii] This was in fact the express purpose of Johan Maurits—Prince of Nassau-Siegen and governor of the Dutch colony in Brazil—who brought the artists Albert Eckhout and Frans Post to Brazil, commissioned the cartoons for the tapestries from them, and went on to use these images as diplomatic currency. Maurits ultimately gifted the cartoons to King Louis XIV of France, and in his 1679 letter to the French Minister of Foreign Affairs, the Marquis des Pomponne, he wrote that in these images one could see all the marvels of Brazil without crossing the ocean.[iii] However, one of the defining characteristics of the tapestry series is that the works are more than a scientific record of this geographic region, presenting a more expansive view of Dutch Brazil. This is especially true of the two tapestries presented here, which depict an African dignitary carried in a litter or hammock by two attendants, and a South American native (Chilean rather than Brazilian) on horseback accompanied by an African groom standing beside another horse. Rather than presenting exoticizing depictions of the people and places portrayed, Eckhout, the primary author of the cartoons, composed an imaginative vision of Brazil that was informed by his firsthand experience and meticulous drawings recording the peoples and places he encountered in the Dutch colony. Much like in the period in which they were created, today these tapestries serve not only as extraordinary records but as captivating images of the people, as well as the flora and fauna, of Africa and South America as they were viewed by Europeans.

The Dutch colony in Brazil was founded and administered by the Dutch West India Company for the purpose of cultivating sugarcane by enslaved labor. Johan Maurits served as governor from 1636–1644. In addition to expanding the colony and founding a new capital, Mauritsstadt (present-day Recife), which became the seat of his European-style court, Maurits initiated a systematic exploration and documentation of Brazil. He brought to Brazil the Dutch scholars Willem Pies and Georg Marcgraft, whose scientific studies resulted in the two-volume Historia naturalis Brasiliae (Leiden, 1648), as well as the Dutch painters Albert Eckhout and Frans Post, who were tasked with making visual records of the territory. While these efforts earned Maurits the present-day reputation of the “humanist prince of the tropics,” his legacy has recently been the subject of re-evaluation, and scholars have brought to light his personal involvement in the trade and ownership of enslaved Africans in Brazil.[iv]

Eckhout was present in Brazil for almost the entirety of Maurits’ tenure, arriving in 1637 and returning to the Netherlands by 1645. During these years he produced a large body of work, including a number of surviving albums of sketches, oil studies, and paintings. Following his return to the Netherlands, Maurits displayed many of the artist’s works at his palace in The Hague—the Mauritshuis—and continued patronizing Eckhout to produce works based on his studies in Brazil. Chief among these were the cartoons for the so-called Anciennes Indes tapestry series, which Maurits commissioned from the artist ca. 1644–1647 (with contributions by Frans Post, who was responsible for the distant landscape views).[v] The subjects of the other tapestries in the series are the Striped Horse, the Two Bulls, the Elephant, the Native Hunter, the Animal Combat, and the Fisherman.

One of the most fascinating aspects of the Anciennes Indes tapestries is the prominent depiction of peoples that one might not expect Eckhout to have encountered in the Dutch colony in Pernambuco. The horseman holding a lance in The Native on Horseback faces away from the viewer, putting on full display his red and poncho, dress local to the Andes. Native also to the region are the two llamas laying in the long grass in the foreground. Given the presence of Andean people and animals in these and other works by Eckhout, it has been plausibly theorized that the artist participated in an expedition to Chile in 1642–1643 that was supported by Maurits and led by Hendrik Brower. The fleet sailed from Mauritsstad with the goal of capturing Valdivia, a former Spanish stronghold on the Pacific coast. They briefly succeeded, renaming the town Brouwershaven, but soon abandoned their settlement after conflicts with the indigenous people, the Mapuche. The Mapuche had adopted the horse after the Spanish introduced them to the New World, and the 17th-century Spanish chronicler Diego de Rosales recorded the adeptness of Mapuche riders at wielding lances, describing them as “grandes hombres de a caballo.”[vi] The principal figure in the tapestry is almost certainly a Mapuche warrior, his horse equipped with tack that must have been specific to this native group. The simple saddlecloth, cane stirrups, and distinctive bridle are here juxtaposed with the European bridle and brocaded silk cloth draped over the dappled horse in the foreground.

While African people would have been a common sight in the Dutch colony—as thousands of enslaved Africans worked on the sugar plantations—the presence of a high-ranking African figure in Eckhout’s tapestry designs has been less conclusively explained. The central figure of the tapestry has traditionally been identified as a king, for which reason it has been submitted that this scene “partially compromised [the tapestries’] scientific value as faithful visual reports of the Dutch colony of Brazil.”[vii] However, while it has been suggested that Eckhout could have visited West Africa with the Dutch forces that departed from Mauritsstad in 1641 and conquered São Paolo de Luanda (Angola) and Axim (Ghana), the composition of The Kongolese Dignitary carried by Two Porters is almost certainly connected with the arrival of five African ambassadors from the Kingdom of Kongo to Mauritsstad in 1642–1643.[viii] Eckhout recorded the appearance these dignitaries in several studies in oil on paper preserved in the Libri picturati, a group of seven albums of sketches from Eckhout’s Brazilian period now in Cracow (Fig. 1). These figures are identifiable as Miguel de Castro, Bastião de Sonho, and António Fernandes, three high ranking and well-educated nobles sent from Soyo to Mauritsstad as ambassadors.[ix] Each wears a red and green mpu cap adorned with shells, and around their necks hang strings of coral beads (particularly favored in Kongo) and metal chains with crosses—undoubtedly to do with the fact that they were a Christian kingdom.[x]

Fig. 1. Albert Eeckhout, Portraits of the Kongo Ambassadors to Mauritsstad, ca. 1642–1644, oil on paper, Jagiellonian Library, Crakow, Libri Picturati 34, folios 1, 3, 5.

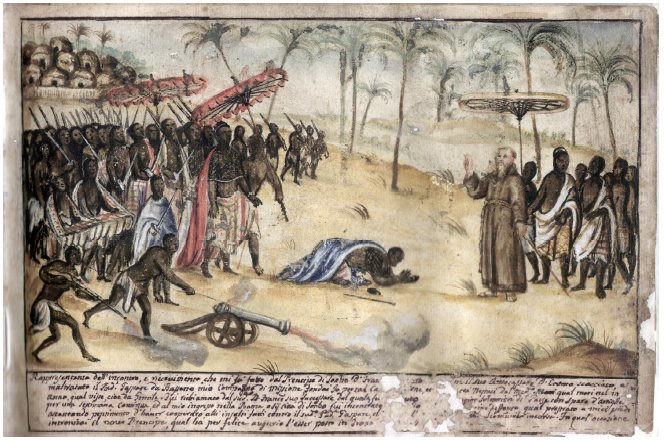

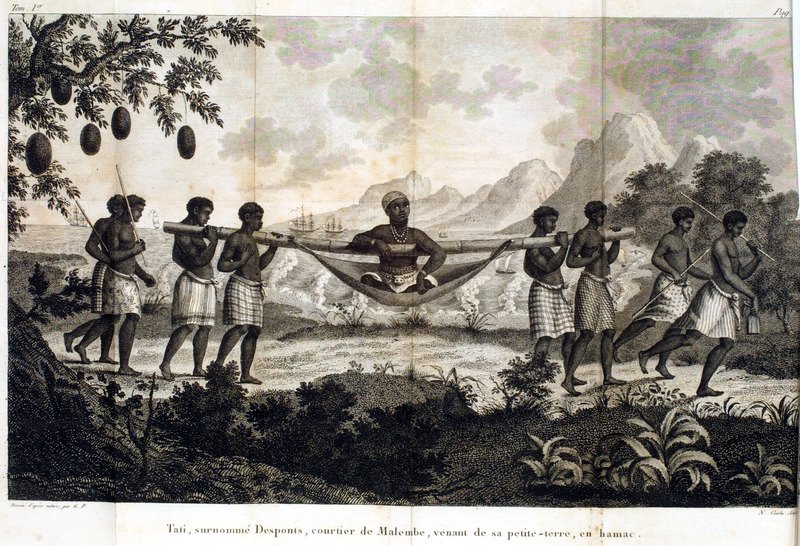

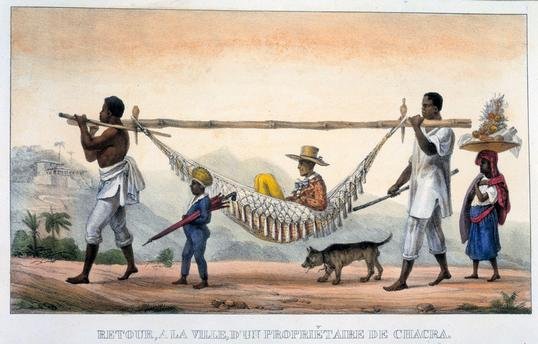

In the tapestry, the figure carried in the litter is dressed in the same garb as the third Kongolese ambassador in the Libri picturati. They each carry a bow and quiver, and they are depicted wearing a yellow brocade wrap tied with a red dyed cloth, a folded animal pelt, and a band of white and blue checkered cotton. The bold, patterned umbrella also appears to emerge from the context of the Kongo kingdom. Although later in date, a similarly depicted umbrella is used to shade a local Kongolese official an illuminated manuscript produced in the mid-18th century by Bernardino d’Asti, a Capuchin friar who trained European novices about apostolic work in Kongo (Fig. 2). The use of litters or hammocks to carry persons of rank is also connected to the Kongo kingdom, and two print sources from the 18th and 19th centuries depicting a Kongolese nobleman and a Brazilian plantation owner carried in this way record the continuation of this practice on both continents (Figs. 3-4). Interestingly, the hammock in the Brazilian print displays a geometric pattern and tassels similar to those in the tapestry, suggesting that the practice of crafting hammocks of this kind was passed down among enslaved Africans in Brazil over the following centuries. In the Brazilian print and in the tapestry the presumably enslaved men carrying the hammocks hold large, forked sticks that were used to hold the hammock aloft when they paused their travel.

Fig. 2. Bernardino d’Asti, A Capuchin Missionary Received by a Local Ruler in Kongo, watercolor on paper, Biblioteca Civica Centrale, Torino, MS 457, fol. 18.

Fig. 3. Louis de Grandpre, Tati, surnommè Desponts, courtier de Malembe, venant de sa petite-terre, en hamac, published in Voyage a la cote occidentale d’Afrique, fait dans les annèes 1786 et 1787, Paris, 1801, vol. 1, p. 99.

Fig. 4. Thierry Frères after Jean-Baptiste Debret, Retour, a la ville, d’un propriétaire de chacra, in Jean-Baptiste Debret, Voyage pittoresque et historique au Brésil, Paris, 1834, plate 15.

The relationships of the scenes depicted in the tapestries to significant moments in the history of the Dutch colony under Maurits’ leadership—a bold expedition to Chile and the arrival of ambassadors from the Dutch allies in Africa—opens interesting questions about Maurits’ role as patron in the creation of the tapestries and his intentions in using them as a diplomatic vehicle. In his final years as governor of the Dutch colony in Brazil, Maurits unsuccessfully attempted to convince the directors of the West India Company to strengthen the relationship between Angola and Brazil and to administer these two territories jointly, presumably under his control.[xi] In commissioning the Anciennes Indes tapestry cartoons from Eckhout, Maurits was not only capturing for his contemporaries images of his domain in Brazil, but also commemorating his achievements in governing of the colony in one of the most treasured artistic mediums of the day. The choice of subject of The Kongolese Dignitary carried by Two Porters is a particularly interesting one, in that it emphasized Maurits’ political ties to Africa and sidelined the realities of enslaved African labor in Dutch Brazil—a system partially enabled by the Kongolese ambassadors, who brought with them to Mauritsstad 200 enslaved people as a gift for Maurits. It is noteworthy that in the tapestry the enslaved people are quite literally pushed to the margins, positioned along the border of the pictorial frame, one turned away from the viewer and the other’s face half disguised by the pole to which the hammock is tied.

Soon after Eckhout completed the cartoons, Maurits engaged the tapestry maker Maximiliaan van der Gucht in Delft to weave two sets of tapestries after the designs. Maurits kept one set for himself and presented the other, along with the Libri picturati, to his cousin Friedrich Wilhelm, the Elector of Brandenberg. Both sets are lost and cannot be traced in documents after the end of the 17th century. Maurits later offered a significant gift of paintings to King Louis XIV of France in 1678–1689—likely connected with the end of the war of 1672–1678 between France and the Netherlands—which included the eight tapestry cartoons and several smaller paintings of Brazilian subjects. With this gift, Maurits likely intended to promote the visual legacy of the Dutch colony in Brazil, which had been lost to the Portuguese in 1654. The cartoons arrived in Paris in 1679 and were put on display in the Salle de la Comédie at the Louvre, where they were greatly admired by the royal family and the court. However, they spent the next eight years in storage; it was not until 1687 that the King approved their being sent to the low-warp workshops of the Gobelins Tapestries Manufactory run by Jean de La Croy and Jean Baptiste Mozin for weaving.[xii]

It has recently been conclusively established that the two tapestries presented here belong to the first edition of the tapestry series. After passing into private ownership, four of the tapestries from this series remained together until the group was split up at the 2007 Alberto Bruni Tedeschi sale. In the years following, it was noted that three of the tapestries from this group, including our Native on Horseback, include on the reverse a patch of the original lining inscribed: “No 158. INDIENS.” This number corresponds with the inventory number assigned to the first series of the tapestries made for the French Royal collection. A second series of tapestries ordered by Louis XIV was woven on the same designs at Gobelins in 1689–1690, inventoried as no. 161 in the Garde Meuble and is today in the Mobilier National of France in Paris (Figs. 5-6).[xiii] The Anciennes Indes tapestries were well-received and became one of the main products of the Gobelins workshops. The cartoons were used to produce six additional official sets of the series—that is, made for the French court or with the permission of the king—which were woven both in high-warp and low-warp versions between 1692 and 1732. After the completion of the eighth set, the cartoons were compromised and could not be reused, but demand for the series had not yet waned.[xiv] Alexandre François Desportes was commissioned to make sketches after the original cartoons and to paint new cartoons, which he did between 1735–1741. These cartoons were used at Gobelin to produce various editions of the so-called Nouvelles Indes series from about 1740 until the beginning of the 19th century.

Of the original first weaving of the Anciennes Indes series, in addition to the present tapestries, the two others from the Bruni Tedeschi sale are in (different) Brazilian collections. The remaining four, with borders removed, hang in the Palacio de Viana in Cordoba (Fig. 7).

Our tapestries have been studied firsthand by Dr. Nello Forti Grazzini, tapestry specialist and author of the entries on the Anciennes Indes and Nouvelles Indes series in the exhibition catalogue Tapestry in the Baroque: Threads of Splendor. We are grateful to Dr. Forti Grazzini for his observations on these works, and a catalogue essay by him is available upon request.

Fig. 5. Gobelins Tapestries Manufactory, The Kongolese Dignitary carried by Two Porters, woven 1689–1690, wool and silk, Mobilier National, Paris, inv. no. GMTT-193-004.

Fig. 6. Gobelins Tapestries Manufactory, The Mapuche Lancer on Horseback, woven 1689, wool and silk, Mobilier National, Paris, inv. no. GMTT-192-003.

Fig. 7. View of the Salon des Gobelinos, Palacio de Viana, Cordoba

[i] The inscription is understood as follows: Set no. 158 of the French Garde-Meuble Royale, The Indians (i.e. the Anciennes Indes series), formed by 8 pieces, 4 aunes high, 3 aunes wide.

[ii] Dr. Nello Forti Grazzini, written report, 10 September 2009.

[iii] Nello Forti Grazzini, “The Striped Horse,” in Tapestry in the Baroque: Threads of Splendor, ed. Thomas B. Campbell, exhibition catalogue, New York, 2008, p. 392, footnote 8.

[iv] Carolina Monteiro and Erik Odegard, “Slavery at the Court of the ‘Humanist Prince’ Reexamining Johan Maurits van Nassau-Siegen and his Role in Slavery, Slave Trade and Slave-smuggling in Dutch Brazil,” Journal of Early American History, vol. 10, no. 1 (September 2020), pp. 3-32.

[v] Although it is generally thought that Eckhout began work on the cartoons after returning to the Netherlands, Forti Grazzini leaves open the possibility that he could have painted them in Brazil. See: Dr. Nello Forti Grazzini, written report, 10 September 2009.

[vi] Monika Lodderstaedt-Dürr, in Exotismus und Globalisierung: Brasilien auf Wandteppichen: die Tenture des Indes, eds. Gerlinde Klatte, Helga Prüßmann-Zemper, and Katharina Schmidt-Loske, Berlin, 2016, pp. 184-186.

[vii] Forti Grazzini, “The Striped Horse,” p. 393.

[viii] The Kingdom of Kongo was founded in the 1300s and encompassed lands south of the Congo River over the western part of today’s Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Republic of the Congo, and Angola. After contact with Portuguese explorers in the 1480s, Nzinga-a-Nkuwu, the fifth ManiKongo, or King of Kongo, voluntarily converted to Christianity, taking the Portuguese name of João I. While he eventually reverted to traditional beliefs, not being able to adopt the Christian tenet of monogamy, his son Alfonso Mvemba a Nzinga established Christianity as the state religion.

[ix] These ambassadors later travelled from Mauritsstad to Amsterdam, where Miguel de Castro was painted in European garments by Jaspar Beckx (now in the Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen).

[x] Cécile Fromont, “Foreign Cloth, Local Habits: Clothing, Regalia, and the Art of Conversion in the Early Modern Kingdom of Kongo,” Anais do Museu Paulista História e Cultura Material, vol. 25, no. 2 (August 2017), pp. 11-31.

[xi] Monteiro and Erik Odegard, “Slavery at the Court.”

[xii] Croy was responsible for The Mapuche Lancer on Horseback and Mozin for The Kongolese Dignitary carried by Two Porters.

[xiii] https://collection.mobiliernational.culture.gouv.fr/objet/GMTT-193-004; and https://collection.mobilier

national.culture.gouv.fr/objet/GMTT-192-003. For a discussion and illustrations of the entire second edition of the tapestry series in the Mobilier National, see: Jean Vittet and Arnauld Brejon de Lavergnée, La collection de tapisseries de Louis XIV, Dijon, 2010, pp. 402-406.

[xiv] In the process of producing the various tapestry editions, the original cartoons had been cut, reattached, and reworked several times. Seven of the eight cartoons are in the collection of the Gobelins Tapestry Manufacture in Paris, but they are in a damaged and fragmentary state.