ORSOLA MADDALENA CACCIA

(Moncalvo, 1596 – 1676)

Madonna and Child

Oil on canvas

32 ½ x 24 ⅝ inches

(82.5 x 62.5 cm)

Provenance:

Private Collection, Germany; by family descent since ca. 1912.

The career and work of Orsola Maddalena Caccia has only recently emerged from scholarly neglect. The reasons for her relative lack of renown are those common to other women artists of the Baroque period. She was, first of all, the daughter and student of a better-known painter, Guglielmo Caccia, called il Moncalvo, and her independent paintings have been confused with and adumbrated by her more celebrated father. And she became a nun at the age of twenty-four, which while undoubtedly limiting practical aspects of a career as an artist, redefined it in fascinating ways. One, however, was to proscribe her working far from her home in the village of Moncalvo, in the province of Asti in Piedmont. For that reason the preponderance of her work has remained in the region to the present day, with few paintings known or studied outside of it, even in Italy.

Baptismal records document that Orsola was born in Moncalvo in 1596 and given the name Theodora.[i] Her mother, Laura Oliva, was herself the daughter of a painter, Antonio Oliva. Theodora is thought to have assisted her father in his studio as early as 1611, at the age of fifteen, and begun to collaborate with him from 1615 on. Significantly, in 1620 Theodora entered the Convent of the Ursulines (Convento delle Orsoline) in Bianzé, about fifty kilometers north of Moncalvo, taking the name of its honoree Orsola Maddalena. The Order was the first to be devoted to the education of girls, and four of Orsola’s sisters were already residents at the convent in Bianzé. It is not known whether Orsola was permitted to continue to paint while resident in the Bianzé convent.

In 1625 Guglielmo Caccia financed the establishment and construction of an Ursuline convent in Moncalvo (now the site of the Museo Civico), locating it adjacent to his own house, and Orsola Maddalena and her sisters soon returned to their hometown. Orsola assisted her ailing father in the completion of several commissions, but in November of that year Guglielmo died. In his will he left his studio and its contents to Orsola and her younger sister Francesca, who entered the convent with the name of Sister Anna Guglielma the following year. No independent works by Francesca, who died young in 1628, have been identified.

The independent career of Orsola Maddalena began in these years and was to continue for fifty more as the “Monacha di Moncalvo” operated her studio within the walls of the convent, teaching novitiates the practice of painting, thereby assuring the survival of their religious community. As a nun she was to become the Abbess of the Convent, and as an artist she would be responsible for over one hundred works in three categories: altarpieces for churches and religious institutions, smaller paintings for domestic devotion, and still-lives reflecting her love of flowers and the belief of the essential divinity of nature. All three aspects can be seen in the ambitious altarpiece of St. Luke in his Studio of ca. 1625, now in the Church of Sant’Antonio di Padova, Moncalvo (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Orsola Maddalena Caccia (with Francesca Caccia?), St. Luke in His Studio, Church of Sant’Antonio di Padova, Moncalvo.

Still-life elements are scattered throughout the painting—books, objects, a dog, bird, and many flowers—while a canvas of the Madonna and Child, quite similar to our painting, rests on an easel—a palette, mixing bowl, and mahlstick nearby. The presence of the bird, a goldfinch, amidst the flowers on Luke’s table may indicate the participation in the painting of Orsola’s sister Francesca, as Guglielmo della Valle, writing in 1793, had stated states that Francesca and Orsola Maddalena distinguished their paintings by including an identifying symbol: a bird for Francesca and a flower for Orsola Maddalena.[ii] The altarpiece was in fact painted for the Convent in Moncalvo, and may have served as a kind of family memorial to Guglielmo Caccia, who, it has sensibly been suggested, is portrayed as Saint Luke.

Our Madonna and Child is a newly discovered painting by Orsola Maddalena, one bearing the hallmarks of her personal style—characterized by a palette tending towards pinks and soft blues, a refined treatment of facial features, a crisp delineation of folds highlighted in white, and an overriding tenderness expressed in gesture and composition. Mary gently embraces the Christ Child, holding him against a cushion, with an array of flowers placed below—a white and pink rose flanking a sprig of lily-of-the-valley, all Marian emblems. The tendency towards ovoid forms and the engaging tilt of the Madonna’s head are traits that appear in other works by the artist, such as one of her few attributable drawings, a Holy Family in Frankfurt (Fig. 2), or a Madonna and Child of similar scale at the Sacro Monte of Oropa in Biella (Fig. 3).[iii] The depictions of the Christ Child both in that painting and ours reflect an endearing conception of children which appears throughout the artist’s oeuvre. Whether as angels, seraphim, infant saints, or the Christ Child, Orsola’s plump babies fly, pray, bless, read, sing, throw flowers, and play musical instruments with delightful innocence (Fig. 4).

Fig. 2. Orsola Maddalena Caccia, Holy Family, pen and ink on paper, Frankfurt, Städel Museum, inv 438.Z.

Fig. 3. Orsola Maddalena Caccia, Madonna and Child, oil on canvas, Sacro Monte of Oropa, Biella.

Fig. 4. Orsola Maddalena Caccia, Detail from the Mystical Marriage of the Blessed Osanna Andreasi, Museo Diocesano Francesco Gonzaga, Mantua.

The Christ Child in our painting holds a piece of fruit in his right hand as he looks directly at the viewer, while the Virgin seems to have a more unfocussed, contemplative engagement, one reflecting an awareness of her son’s fate. Much the same emotional disparity appears in the Madonna and Child with St. John the Baptist, recently acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, a work also graced by a display of flowers (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Orsola Maddalena Caccia, Madonna and Child with St. John the Baptist, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

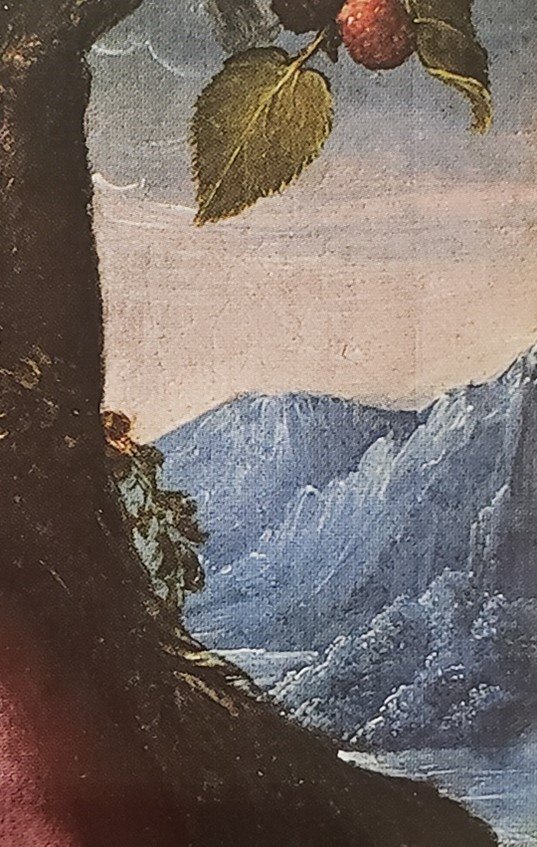

While the presence of flowers in these paintings may be a kind of disguised signature, another motif, one that likely had as well personal significance for the artist, appears in our Madonna, the Metropolitan Museum painting, and other works by Orsola Maddalena—the distant mountainous landscape. Though varying in specific form, these austere, mountainous landscapes, uniformly cast in a spectral blue light, appear in many of the artist’s works. Treeless and occasionally topped with snow, these recall the appearance of the Alpine peaks visible from Moncalvo and the surrounding countryside (Figs. 6-10).

The paucity of documented works prohibits a firm dating of our painting, but a placement in the 1630s or 1640s seems likely. The painting has remarkably survived in excellent condition on its original seamed canvas, which has not been lined.

We are grateful to Dr. Antonella Chiodo for confirming the attribution to Orsola Maddalena Caccia (written communication, 24 May 2022). Dr. Chiodo will be including the painting in her forthcoming monograph on the artist.

Fig. 6. Detail of the present work.

Fig. 7. Detail of the Madonna and Child with St. John the Baptist, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 8. Detail of the Madonna and Sleeping Child, Sant’Eusebio, Bianzé.

Fig. 9. Detail of the Madonna and Child, Private Collection, Piemonte.

Fig. 10. Two views of the landscape north of Moncalvo.

[i] For documentation of Orsola Maddalena Caccia’s life and career, see: Antonella Chiodo, “Note in margine alla vita e alle opera di una monaca pittore,”Archivi e storie, vols. 21-22 (Jan-Dec 2003), pp. 153-202, and the recent exhibition catalogue Orsola Maddalena Caccia, San Secondo di Pinerolo, Fondazione Cosso, 2012.

[ii] Guglielmo della Valle, Notizie degli artefici piemontesi (1793–1794), ed. G. C. Sciolla, Turin, 1990, pp. 93-94. This is also repeated by Luigi Lanzi, Storia Pittorica dell”Italia (1796), ed. Florence 1974, vol. 3, pp. 243-244.

[iii] Antonella Chiodo, in Le Signore dell’Arte, exh. cat., Milan, 2021, p. 136.