LUDOVICO CARRACCI

(Bologna, 1555-1619)

The Vision of Saint Jerome

Oil on canvas

16 ⅛ x 12 ¼ inches (41 x 31 cm)

Provenance:

Probably Sampieri Collection, Palazzo Sampieri Senatorio, Bologna, by the late 18th century

Private Collection, England, as Guercino, until 1933; when acquired by:

Hermann Voss, Berlin and Wiesbaden, 1933–1937; by whom sold to:

Galerie Stern, Düsseldorf; their forced sale, “Die Bestände Der Galerie Stern Düsseldorf,” Lempertz, Cologne, 13 November 1937, lot 181; where acquired by:

Private Collection, Rhineland, Germany

Private Collection, Zürich, Switzerland, by whom sold, Lempertz, Cologne, 20 May 2000, lot 625; where acquired by:

Richard L. Feigen, New York, 2000–2009; by whom voluntarily restituted to the heirs of Max Stern:

Dr. and Mrs. Max Stern Foundation, Montreal, 2009–present

Exhibited:

“Italienische Malerei des 17. und 18. Jahrhunderts,” Wiesbaden, Nassauisches Landesmuseum, May–June 1935, as Ludovico Carracci, lent by Hermann Voss, and on long-term loan to the museum until 1937.

Montreal, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, 2009–2018.

Copies:

Engravings

1) Wandutius Aurifex, ca. 1670, inscribed “Wandutius Aurifex fecit” and “Lodovicus Carratius In,” Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Kupferstich-Kabinett.

2) Anonymous (possibly by Ludovico Mattioli), Lambertini Album XIII, Pinacoteca Nazionale, Bologna, no. 5273.

Drawings

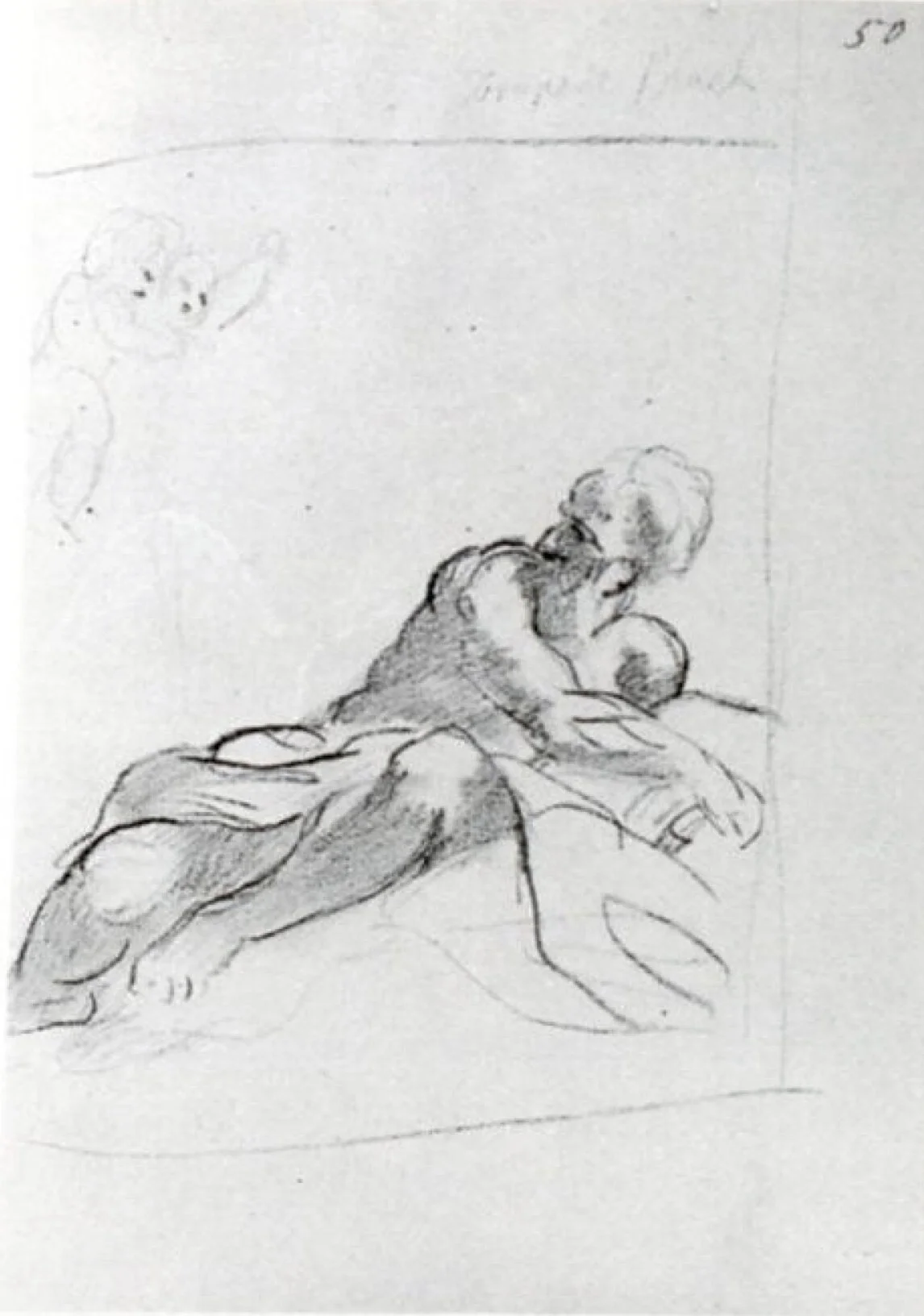

1) Sir Joshua Reynolds, pencil, pen and ink, foglio 50r in Copland-Griffiths sketchbook no. 61, Plymouth City Museum & Art Gallery, inv. no. 2014.72.

Paintings

1) After Ludovico Carracci, oil on canvas, 15 x 11 inches (38.1 x 27.9 cm), Christie’s, New York, 23 January 2004, lot 169.

2) After Ludovico Carracci, oil on canvas, 16 ½ x 13 ½ inches (42 x 34 cm), Dorotheum, Vienna, 10 December 2015, lot 115.

3) After Ludovico Carracci, dimensions unknown, private collection, consigned to Dorotheum, Vienna in 2011 (according to Brogi, 2016, pp. 119-120, footnote 187, fig. 148).

4) After Ludovico Carracci, dimensions unknown, Vatican Museums, Vatican City (according to Brogi, 2016, p. 120, footnote 187).

Literature:

Marcello Oretti, Le pitture che si ammirano nelli palaggi e case de’ nobili città di Bologna, manuscript, Bologna, Biblioteca Comunale, MS. B.104, ca. 1760-80, foglio 29, “Un piccolo Quadretto con un S. Girolamo, tiene in mano un teschio di morte, da un piede il Leone, e due Angioletti in aria, quasi simile a quello di Lodovico, in S. Martino, è delli Carracci,” as in the Palazzo Sampieri Senatorio dalla Mercanzia.

1783 Inventory of the Palazzo Sampieri Senatorio, Biblioteca Comunale dell’Archiginnasio di Bologna, fondo speciale Talon Sampieri, B 344, fasc. 132, “Inventario e stima de quadri esistenti nella casa senatoria Sampieri, stimate dal signor Pedrini,” c. 3v. “Due quad: piccoli un rap: S. Girolamo, e l’altro S. Franco: di Lodovico Caracci, con cornice intagl: e dorato.”

Hermann Voss, “Quellenforschung und Stilkritik: Eine Praktische Methodik mit Beispielen aus der Spätitalienischen Malerei,” Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte, vol. 2, no. 3 (1933), pp. 191-192, fig. 8, as Ludovico Carracci.

Italienische Malerei des 17. und 18. Jahrhunderts: Katalog der von der Stadt Wiesbaden und dem Nassauischen Kunstverein Veranstalteten Ausstellung, Wiesbaden, 1935, p. 8, cat. no. 54, as Ludovico Carracci.

“Auflösung der Galerie Stern,” Internationale Sammler-Zeitung, no. 19 (1 December 1937), p. 205, as sold for 4800 Reichsmark.

Die Weltkunst, vol. 11, no. 42/43 (24 October 1937), p. 5.

Die Weltkunst, vol. 11, no. 46 (21 November 1937), p. 6.

Heinrich Bodmer, Lodovico Carracci, Burg bei Magdeburg, 1939, p. 142, as attributed to Ludovico by Hermann Voss.

Gail Feigenbaum, Lodovico Carracci, A Study of His Later Career and a Catalogue of his Paintings, PhD dissertation, Princeton University, 1984, pp. 255-256, cat. no. 37, fig. 54, in catalogue A, as Ludovico Carracci

Emilia Calbi and Daniela Scaglietti Kelescian, Marcello Oretti e il Patrimonio Artistico Privato Bolognese: Bologna, Biblioteca Comunale, MS. B.104, Bologna, 1984, p. 59.

Alessandro Brogi, “Il fregio dei Carracci con “Storie di Romolo e Remo” nel salone di palazzo Magnani,” in Il Credito Romagnolo fra storia, arte e tradizione, Bologna, 1985, p. 246, as Ludovico Carracci.

Giovanna Perini “‘L’uom più grande in pittura che abbia avuto Bologna’ – L’alterna fortuna critica e figurative di Ludovico Carracci,” in Ludovico Carracci, ed. Andrea Emiliani, Milan, 1993, pp. 315-316, footnote 287; Appendix 2: “Elenco Sommario delle Stampe da Ludovico Carracci,” p. 341, no. 38, as Ludovico Carracci.

Catherine MacKenzie, ed., Auktion 392: Reclaiming the Galerie Stern, Düsseldorf, exhibition catalogue, Montréal, Faculty of Fine Art Gallery, Concordia University; New York, Leo Baeck Institute; London, Ben Uri Gallery; Jerusalem, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 20 October 2006-31 August 2008, pp. 17, 50, no. 185.

Laurence Kanter and John Marciari, Italian Paintings from the Richard L. Feigen Collection, New Haven, 2010, p. 130, footnote 5, as Ludovico Carracci.

Giovanna Perini Folesani, “Riflessioni baroccesche tra Bologna e Urbino,” in Barocci in Bottega, ed. Bonita Cleri (Urbino, 2012), Macerata, 2013, p. 39, footnote 104, as Ludovico Carracci.

Sara Angel, “The Secret Life of Max Stern,” The Walrus (15 October 2014).

Alessandro Brogi, Ludovico Carracci (1555-1619), Bologna, 2001, vol. 1, pp. 271-273, cat. no. R51, under rejected attributions; and vol. 2, fig. 291, as Bolognese painter, second half of the seventeenth century; p. 298, cat. no. P103, the Saint Jerome in the Desert documented in the Palazzo Sampieri listed under lost or dispersed works.

Giovanna Perini Folesani, Sir Joshua Reynolds in Italia (1850-1752): Passaggio in Toscana, Il taccuino 201 a 10 del British Museum, Florence, 2012, pp. 90-91, footnote 196, as Ludovico Carracci.

Alessandro Brogi, Ludovico Carracci: Addenda, Bologna, 2016, pp. 116, 118-120, footnotes 178, 184-185, fig. 146, as “after Ludovico Carracci (?),” a copy after the lost original by Ludovico Carracci in the Sampieri collection.

Christie’s, New York, Property from the Collection of Richard L. Feigen, 1 May 2019, under lot 26, as Ludovico Carracci.

Giovanna Perini Folesani, Sir Joshua Reynolds in Italia - Il soggiorno romano - I - il taccuino di Plymouth, Florence, forthcoming, as Ludovico Carracci.

With its dynamic composition and jewel-like refinement, this devotional work is a prime example of the small-scale paintings executed by Ludovico Carracci, the preeminent painter in late sixteenth-century Bologna. Along with his younger cousins Agostino and Annibale, Ludovico helped introduce a new naturalism to contemporary painting as head of the family’s Accademia degli Incamminati—literally “the academy of the progressives.” The artistic reform ushered in by the Carracci was a watershed moment in the history of painting in Italy, effectively putting an end to the dominant Mannerist style and making way for the Baroque. With its earthy tones, graceful forms, and dramatic lighting effects, the present work exemplifies the mature style that was emulated by Ludovico’s pupils, chief among them, Guercino. In fact, the art historian and former owner of the painting, Hermann Voss, once cited our Saint Jerome as “proof of the influence that Ludovico had over Guercino.”[i] Ludovico’s style moved in a different direction later in his career, his works characterized by their monumentality and eccentricity. However, it was the earlier, small devotional and cabinet paintings like this one that exerted the greatest influence on the next several generation of Bolognese painters.

Saint Jerome was an early Christian priest and theologian, best known for his Latin translation of the Bible, the Vulgate. He spent several years as a penitent hermit in the Syrian desert—which is how he is depicted here, naked and covered only by dark blue drapery that billows over his legs onto the rocky earth. At his feet rests a lion, his legendary companion tamed after he healed its injured paw. The saint is shown receiving divine inspiration through the agency of two putti floating above a dark cloud at the upper left. He turns to them and away from the skull, the traditional symbol of the transience of human life, and the book, an allusion to his celebrated translation. Ludovico has masterfully created gentle torsion in the saint’s uncovered body as he reaches towards the right edge of the painting while turning his head left to witness the heavenly apparition (Fig. 1). A swathe of bright blue sky and distant landscape cuts diagonally across the composition, creating both a dramatic abstract division between the divine and the earthly, and a vector that connects the saint and his visitants.

Fig. 1. Detail of the present painting.

Our Saint Jerome was first published in 1933 by Hermann Voss, who attributed the painting to Ludovico in part on the basis of a print signed Wandutius Aurifex that recorded the composition and attributed its design to the artist (Fig. 2).[ii] The composition of the painting is also recorded in a second engraving (Fig. 3), possibly by the Bolognese artist Ludovico Mattioli,[iii] which is similarly executed in reverse orientation to the present work. As Voss and several subsequent scholars have noted, the pose of Saint Jerome is strikingly similar to that of the angel in the upper right of Ludovico’s 1594 Vision of Saint Hyacinth in the Louvre (Fig. 4). Alessandro Brogi has questioned Ludovico’s authorship of this composition based on this resemblance, claiming that the artist never repeated the pose of a figure in two of his works.[iv] However, Babette Bohn has noted that in the period of 1594–1598 Ludovico “particularly favor[ed] arms and/or legs traversing the body, as Jerome’s right arm does here.”[v] Ludovico frequently employed this motif in both paintings and drawings in these years, and the position of Jerome in the present work is especially close to that of his counterpart in his study for the Angel Warning Saint Joseph to Flee to Egypt of ca. 1595–1596 (Fig. 5).[vi] A date for the present painting around 1594–1598 seems particularly appropriate, as this is also the period in which Ludovico executed his grand altarpiece of Saint Jerome for the church of San Martino in Bologna.

Fig. 2. Wandutius Aurifex, engraving after Ludovico Carracci, Saint Jerome.

Fig. 3. Anonymous (possibly by Ludovico Mattioli), engraving after Ludovico Carracci, Saint Jerome.

Fig. 4. Detail of Ludovico Carracci, Vision of Saint Hyacinth, Paris, Louvre.

Fig. 5. Ludovico Carracci, Study for the Angel Warning Saint Joseph to Flee to Egypt, whereabouts unknown.

In her 1984 dissertation on Ludovico Carracci, Gail Feigenbaum associated our Saint Jerome with paintings described in two eighteenth-century collection inventories. The 1701 inventory of the collection of Louis Bauyn, Seigneur de Cormery, lists: “a painting on wood, fourteen poulces high by six poulces wide, with a gold frame, representing St. Jerome, with a skull and a book under his hand, a lion at his feet, and two small angels up above, all in a landscape, painted by Ludovico Carracci.”[vii] Additionally, in the late-eighteenth century the Bolognese nobleman and cataloguer Marcello Oretti recorded in his list of works in the Sampieri collection “a small painting with a Saint Jerome who holds a skull in his hand with a lion at his feet with two small angels in the air, similar to that by Ludovico in San Martino, it is by the Carracci.”[viii] Scholars have rightly noted that our Saint Jerome could not be the one from the collection of Louis Bauyn, as that work is described as painted on panel.[ix] However, there is general agreement that the painting recorded by Marcello Oretti in the Sampieri collection was the original autograph painting of the composition by Ludovico, on which the prints discussed above are based.

The Sampieri possessed one of the most celebrated collections in Bologna. The paintings were displayed in the quadreria (paintings gallery) on the ground floor of the family’s palazzo on the Strada Maggiore (no. 244, today no. 24), which was decorated with frescoes by Ludovico, Agostino, and Annibale Carracci. The fame of the quadreria Sampieri stretched far beyond Bologna, and it was a popular destination for locals and visitors to the city, especially artists. Sir Joshua Reynolds, a great admirer of Ludovico Carracci, made a drawing after our Saint Jerome in a sketchbook that he used to record details and entire compositions of paintings that he encountered on his journey through Italy between 1751–1752 (Fig. 6).[x] This sketch, which must have been executed during Reynolds’ visit to Bologna in July 1752, faithfully reproduces the seated saint and the two angels above him. Several weak copies after the present painting, all similar in scale, are also known.[xi] The existence of these copies may be explained by the fact that works in the Sampieri collection—including Annibale Carracci’s Burial of Christ in the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Virgin and Child with Saint Lucy formerly in the Richard L. Feigen collection—were easily accessible and frequently copied by artists.

Fig. 6. Sir Joshua Reynolds, sketch after Ludovico Carracci,

Plymouth City Museum & Art Gallery.

It is not known when the Saint Jerome by Ludovico Carracci entered the Sampieri collection. However, it is conceivable that the painting might have been commissioned by Abbate Astorre di Vincenzo Sampieri, an important early patron of the Carracci. Interestingly, it has not been previously recognized in the literature that Marcello Oretti records our Saint Jerome in the Palazzo Sampieri Senatorio (73 Via Santo Stefano, near the Loggia dei Mercanti or Palazzo della Mercanzia), rather than in the main Sampieri palazzo on the Strada Maggiore that was home to the famous quadreria.[xii] The painting was later listed in the 1783 inventory of the Palazzo Sampieri Senatorio, which explains why the Saint Jerome does not appear in any of the eighteenth century inventories of the Palazzo Sampieri on the Strada Maggiore, nor in any written descriptions of the quadreria.[xiii] While it is possible that our Saint Jerome was in the Sampieri palazzo on the Strada Maggiore at an earlier date, it must have been in the Palazzo Senatorio that Sir Joshua Reynolds, and possibly also the engravers and the copyists, encountered this work.

Luigi Sampieri was the proprietor of the Palazzo Sampieri Senatorio in the late eighteenth century.[xiv] Following the death of the heirless Padre Ferdinando Francesco Sampieri, the last living member of the main branch of the Sampieri family, Luigi inherited the Strada Maggiore palace and the collection of paintings it contained in 1787.[xv] The documents attest that some (but not all) of the pictures from the collection at the Palazzo Senatorio were at this point brought to the quadreria on the Strada Maggiore.[xvi] This includes Francesco Francia’s Virgin and Child with Saints Dominic and Barbara in The Morgan Library and Museum, here newly identified as originating from the Sampieri collection.[xvii] However, our Saint Jerome was not among the works transferred to the quadreria.[xviii] It must have remained in the collection at the Palazzo Senatorio, but unfortunately it has not yet been possible to determine when our painting left the Palazzo Senatorio or when it was sold by the Sampieri.

The attribution of our Saint Jerome to Ludovico Carracci and its identification as the original work in the Sampieri collection has been accepted by art historians both before and after the painting’s reemergence in 2000. In addition to those scholars cited in the literature (Voss, Perini, and Feigenbaum), the painting has recently been studied firsthand by Laurence Kanter, John Marciari, and Babette Bohn—all of whom have endorsed Ludovico’s authorship of the present painting.[xix] Dr. Bohn has commented: “The composition of the picture (with little middle-ground transition from near to far), the complex pose of Saint Jerome, with head, right arm, and legs all oriented in various directions to create a dynamic resolution for the figure that expresses his spiritual excitement, and above all the wonderfully expressive head of Saint Jerome, all confirm the autograph status of the picture around 1594–1598” (written communication, 6 October 2019). She notes as well the relationship of the present painting with Ludovico’s Saint Hyacinth in the Louvre and Ludovico’s drawings from these years.[xx] However, Alessandro Brogi, who had previously accepted the painting as by Ludovico but knows the painting only through photographs, has called into question the authorship of the painting and suggested that it is an old copy of the painting from the Sampieri collection, which he considers lost.[xxi]

Provenance Notes

Our Saint Jerome was first published in 1933 by Hermann Voss, one of the most prominent German art historians of the twentieth century. In his publication, Voss reported that the Saint Jerome was in a private collection in Berlin and that it had previously been in a private collection in England where it was considered the work of Guercino. It has gone unnoticed in the scholarly literature on Ludovico Carracci, as well as on Hermann Voss’s collecting activities, that Voss was then the owner of the painting.[xxii] After having worked for nearly a decade as a curator at the Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum, Voss departed Berlin for London in 1933 in search of new career opportunities, bringing his personal library and paintings collection with him.[xxiii] However, his application for a British visa was denied in 1934 on the grounds that he was not suffering religious, racial or political persecution, and he returned to Germany, taking up a position as the director of the Nassauisches Landesmuseum in Wiesbaden.[xxiv]

Voss lent the Saint Jerome, along with several other works from his personal collection, to the exhibition of seventeenth and eighteenth century Italian paintings that he organized at the museum in Wiesbaden in 1935.[xxv] It was also on long-term loan to the museum and on view in the permanent collection.[xxvi] The Saint Jerome was likely in Voss’s possession by the time of his 1933 article, but he is known to have avoided publicizing the fact that he personally owned some of the paintings that he published and exhibited throughout his life.[xxvii] Furthermore, given that Voss was in England in 1933, it is probable that he acquired the work during his brief tenure there. However, it is still not known from whom he acquired it.[xxviii] Given that Voss notes that the painting was previously in an English private collection, it is possible that he could have acquired it directly from the previous owner or through a dealer.

Voss sold the Saint Jerome along with a landscape by Laurent de La Hire to the Galerie Stern in exchange for Das Mädchen aus der Fremde by Josef Anton Koch in February 1937.[xxix] The Düsseldorf-based art dealer Leo Pauly acted as Voss’s agent or intermediary in the exchange, and it is not clear if Max Stern knew that the Saint Jerome was coming from Voss’s personal collection.[xxx] Voss’s acquisition of Koch’s Das Mädchen aus der Fremde has been discussed by Kathrin Iselt, who noted that “it is not known at what price and when exactly Voss acquired the [Koch] painting from Max Stern.”[xxxi] This previously unknown transaction finally clarifies the circumstances of how Voss acquired Das Mädchen aus der Fremde and how this painting by Ludovico Carracci arrived at the Galerie Stern.

The Galerie Stern was established in 1913 by the German-Jewish art dealer Julius Stern and rose to prominence as one of the leading galleries in the city, specializing in paintings by established artists of the Düsseldorf school, nineteenth century German works, and Old Masters. Julius’s son Max Stern joined the gallery in 1928 after completing his PhD in art history. Over the course of the following decade, the Galerie Stern suffered great difficulties brought on first by the global economic downturn and later by the rise of Nazism in Germany. As a result of the Great Depression, the Galerie Stern, like many other art galleries, began to hold auctions, operating as the Kunstauktionshaus Stern between 1931 and 1933. However, this activity came to a halt in 1933 after Adolf Hitler rose to power as chancellor of Germany. The gallery was subjected to a new regulation that prevented Jews from conducting public auctions. From this point, the Galerie Stern focused on mounting large exhibitions at the gallery, which in reality were nothing more than auctions in disguise. During this period, Max Stern took over management of the gallery and subsequently inherited it after the death of his father in October 1934. Not long thereafter, the Galerie’s activity was again halted by the Nazi authorities. Max Stern was notified in August 1935 by the President of the RKdbK (the Reichskammer der Bildenden Künste, or Reich Chamber for the Fine Arts) that he could no longer continue his profession as an art dealer due to his “race.” Max appealed this decision and fought several subsequent orders to sell or dissolve the Galerie Stern. However, on 13 September 1937 Max received a final letter stating that no further appeals would be considered. He was given until 15 December of that year to liquidate the gallery’s holdings and to cease operation, which resulted in the stock of the gallery being offered at a forced auction at Lempertz in Cologne on 13 November 1937.[xxxii]

The Saint Jerome came into Max Stern’s possession not long before the forced sale of the Galerie Stern at Lempertz. The importance of the Saint Jerome was clearly recognized by Stern, who acquired it for his gallery’s stock despite already being under intense pressure from the Nazis to close his business, as well as by the organizers of the auction at Lempertz in the period leading up to the sale. The entry on the painting in the auction catalogue included a long quotation from Hermann Voss’s 1933 article and reported that the painting had been on loan to the museum in Wiesbaden. In addition to being featured as the first lot offered in the section of ‘Alte Meister’ paintings in the Lempertz sale, the Saint Jerome was listed among the paintings on offer in the advertisements for the highly publicized auction (Fig. 7). The painting made the second highest price of all of the “Alte Meister” paintings in the sale at 4800 Reichsmark, surpassed only by the Philips Wouwerman, which sold for 5000.[xxxiii]

As with nearly all of the works from the Galerie Stern forcibly sold at Lempertz in 1937, excepting Winterhalter’s Girl from the Sabine Hills, the identity of the buyer of the Saint Jerome at the sale is unknown. Although the prices paid for the paintings at the Stern sale were reported in Die Weltkunst and the Internationale Sammler-Zeitung in 1937, these publications do not record the names of the buyers. Additionally, Lempertz’s auction records were destroyed during the bombing of Cologne in 1943, making it impossible to identify the buyers at the sale.

When the Saint Jerome reappeared at auction at Lempertz in May 2000, it was listed as having been in a private collection in the Rhineland following the 1937 sale, and then in a private collection in Zürich, likely the consignor of the painting to the 2000 sale.[xxxiv] The painting was there purchased by the New York dealer and collector Richard L. Feigen for his personal collection. The Saint Jerome was originally slated to be included in the exhibition of Italian paintings from his collection at the Yale University Art Gallery in 2010. However, shortly before the exhibition Feigen learned of the circumstances of the 1937 Galerie Stern auction and voluntarily returned the Saint Jerome to the Dr. and Mrs. Max Stern Foundation.[xxxv] The exhibition catalogue thus only briefly mentioned the Saint Jerome (with an attribution to Ludovico Carracci in full).[xxxvi]

Max Stern was able to leave Germany in 1937, first traveling to London, where he was interned in 1940 on the Isle of Man as an enemy alien; then to Canada, where internment greeted him as well, although he was released in 1941. He moved to Montreal and was able to find work at the newly-established Dominion Gallery. There, having acquired a passionate interest in contemporary Canadian artists to complement his knowledge of European painting, he flourished. Over the years he became a partner in the gallery and eventually came to own it (Fig. 10). His distinguished career as an art dealer in Canada could only partially compensate for the dire situation that forced him to leave his native country. Stern never stopped seeking the return of paintings that he had been forced to abandon or sell at auction in Germany.

Ludovico Carracci’s Saint Jerome is now being sold for the benefit of the Max Stern Art Restitution Project, to further the recovery of works expropriated from Max Stern and to support related research and educational programs.

Fig. 8. Yousuf Karsh, Portrait of Max Stern, 1973.

[i] Hermann Voss, “Quellenforschung und Stilkritik: Eine praktische Methodik mit Beispielen aus der spätitalienischen Malerei,” Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte, vol. 2, no. 3 (1933), p. 191. When the painting was in a private collection in England, it had even been attributed to Guercino.

[ii] The identity of Wandutius Aurifex is unknown, but he is generally assumed to be Bolognese. This is the only print signed by or attributed to the artist, and it is thought to date from around 1670. Wandutius is sometimes cited with the Italian form of his name, Vanducci Orefice. The Vanducci were an ancient noble family in Bologna, and it is possible that this goldsmith came from their ranks. For references to Wandutius Aurifex, see: Ulrich Thieme and Felix Becker, Allgemeines Lexikon der bildenden Künstler von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart, vol. 34, 1940, p. 94; Pietro Zani, Enciclopedia metodica critico-ragionata delle belle arti, part 1, vol. 19, Parma, 1824, p. 44; and Karl Heinrich von Heinecken, Dictionnaire des artistes, dont nous avons des estampes, avec une notice detaillee de leurs ouvrages gravés, vol. 3, Leipzig, 1789, p. 626.

[iii] Giovanna Perini “‘L’uom più grande in pittura che abbia avuto Bologna’ – L’alterna fortuna critica e figurative di Ludovico Carracci,” in Ludovico Carracci, ed. Andrea Emiliani, Milan, 1993, p. 316.

[iv] Alessandro Brogi, Ludovico Carracci: Addenda, Bologna, 2016, p. 119.

[v] Written communication, 8 July 2019.

[vi] Babette Bohn, Ludovico Carracci and the Art of Drawing, Turnhout, 2004, pp. 263–264, cat. no. 130. This drawing is a study for a lost painting by Ludovico, of which there is a copy in the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Bologna (Zambeccari collection, inv. no. 351).

[vii] Gail Feigenbaum, Lodovico Carracci, A Study of His Later Career and a Catalogue of his Paintings, PhD dissertation, Princeton University, 1984, pp. 255–256. Transcribed in: Daniel Wildenstein, Inventaires après déces d’artistes et de collectioneurs français du xviii siècle, Paris, 1967, p. 9, “No. 459 Item un tableau sur bois ayant quatorze poulces de haut sur dix poulces de large, avec sa bordure dorée, representant un Saint Hiérosme, appuyé sur une teste de morte et un livre sous sa main, un lyon a ses pieds et deux petits anges en haut, le tout dans un paysage, peint. par Louis Carrache pris....350 l.”

[viii] Marcello Oretti, Le pitture che si ammirano nelli palaggi e case de’ nobili città di Bologna, manuscript, Bologna,

Biblioteca Comunale, MS. B.104, ca. 1760–80, foglio 29. Transcribed in: Emilia Calbi and Daniela Scaglietti Kelescian, Marcello Oretti e il Patrimonio Artistico Privato Bolognese: Bologna, Biblioteca Comunale, MS. B.104, Bologna, 1984, p. 59, no. [b] 29/9. For biographical details on Oretti, see: Giovanna Perini, “Nota Biographica,” in Marcello Oretti, Raccolta di alcune marche e sottoscrizioni praticate da pittori e scultori, Florence, 1983, pp. III–XV.

[ix] John Marciari, unpublished catalogue entry on the Vision of Saint Jerome, written in preparation for the exhibition Italian Paintings from the Richard L. Feigen Collection in 2010. Marciari notes: “The passage of the painting from Bologna to France and back again within the eighteenth century is improbable, and moreover, the Sampieri were important early patrons of the Carracci, and their collection remained intact until the late eighteenth century. The most likely scenario is that the picture in France was a copy after a Sampieri original. There is ample evidence that the Sampieri pictures were often copied, and Ludovico seems never to have used panel supports for pictures of this type (the only pre-1600 panel paintings generally accepted as his work are the musicians in the Hercolani collection, Bologna, which are evidently fragments of a cantoria from Palazzo Fava).”

[x] This drawing is foglio 50r in Copland-Griffiths sketchbook no. 61, one of the two Reynolds sketchbooks formerly in the Copland-Griffiths collection, which was acquired by the Plymouth City Museum & Art Gallery in 2014 (inv. no. 2014.72). For a full reference to the sketchbook, see: Nicholas Penny, Reynolds, exh. cat., Royal Academy, London, 1986, p. 334, cat. no. 159. Reynolds’ inscription in the upper right of the drawing reads ‘Draperie Black.’

[xi] Alessandro Brogi has proposed that a painting previously with Dorotheum in Vienna but never offered at auction, is possibly older than the present work, which he does not consider to be by Ludovico. Brogi also mentions another painted copy in the collection of the Vatican Museums. We have not been able to locate an image of this work. See: Brogi, Ludovico Carracci: Addenda, pp. 119–120, footnote 187.

[xii] The Palazzo Sampieri Senatorio was another historic palace that was in the possession of the family from the year 1467 on. By the eighteenth century, the palazzo was owned by a different branch of the Sampieri family than the main branch that resided in the Strada Maggiore palace. See: Giancarlo Roversi, Palazzi e case nobili del ‘500 a Bologna: la storia, le famiglie, le opere d’arte, Bologna, 1986, pp. 337–339; and Giancarlo Roversi, “Residenze Senatorie Bolognesi,” in I Palazzi Senatorii a Bologna. Architettura Come Immagine del Potere, ed. Giampiero Cuppini, Bologna, 1974, p. 316. The Palazzo Senatorio also housed a collection of paintings, including a family chapel frescoed by Ercole Graziani. See: Claudia di Sturco, “Fonti Catastali Bolognesi: Analisi della Proprietà Nella Strada S. Stefano Tra XVIII e XIX Secolo,” unpublished thesis, Università di Bologna, 2007, p. 51.

[xiii] For the 1783 inventory of the Palazzo Sampieri Senatorio, see: Biblioteca Comunale dell’Archiginnasio di Bologna, fondo speciale Talon Sampieri, B 344, fasc. 132, “Inventario e stima de quadri esistenti nella casa senatoria Sampieri, stimate dal signor Pedrini,” 1783, c. 3v. “Due quad: piccoli un rap: S. Girolamo, e l’altro S. Franco: di Lodovico Caracci, con cornice intagl: e dorato.” The earliest inventories of the Sampieri collection in the palazzo on the Strada Maggiore all date from the eighteenth century: 1718 (BCABo, fondo speciale Talon Sampieri, B.62, fasc. 86); 1743 (BCABo, fondo speciale Talon Sampieri, B.344, fasc. 132 and another version cited in Giuseppe Campori, Raccolta di cataloghi ed inventarii inediti, Modena, 1870, pp. 598–602); 1746 (BCABo, fondo speciale Talon Sampieri, B.344, fasc. 132); and 1787 (BCABo, fondo speciale Talon Sampieri, A.219, fasc. 7). Carlo Cesare Malvasia, Le pitture di Bologna, Bologna, 1686; Carlo Cesare Malvasia, Pitture scolture ed architetture delle chiese, luoghi pubblici, palazzi, e case della città di Bologna, e suoi sobborghi, Bologna, 1792; and Luigi Lanzi, “Viaggio specialmente del 1782 per Bologna, Venezia, la Romagna,” ms. 36/I, Biblioteca della Galleria degli Uffizi, Firenze (published by Giovanna Perini in Ludovico Carracci, 1993, pp. 335–337).

[xiv] “Sampieri Luigi: 27 Gennaio 1758–13 Agosto 1797,” Storia e Memoria di Bologna, https://www.storia

ememoriadibologna.it/sampieri-luigi-481067-persona.

[xv] Angelo Mazza, “Sulle tracce del ‘Ballo degli amorini’ di Francesco Albani. Vicende settecentesche della Galleria Sampieri, ‘superbissimo museo’,” in La Danza degli amorini (1623–1625) di Francesco Albani: una favola mitologica come dono nuziale, exh. cat., Milan, 2014, pp. 35–37.

[xvi] For the 1788 inventory of paintings added to the quadreria, see: BCABo, fondo speciale Talon Sampieri, B.344, fasc. 132, “Quadri aggiunti nella Galleria da Sua Eccza Sig. Marse. Senat.re Luigi Sampieri Padrone della medma.,” 1788.

[xvii] https://www.themorgan.org/objects/item/103130. For a brief discussion of the movement of works from the Palazzo Sampieri Senatorio to the Strada Maggiore, see: Marinella Pigozzi, “La Collezione Sampieri, Dalla Dispersione alla Negazione, All’Auspicabile Valorizzazione,” Intrecci d’arte Dossier, no. 3 (2018), pp. 51–52, footnote 30.

[xviii] It does not appear in the 1795 catalogue of the Sampieri quadreria (Descrizione Italiana e Francese di tutto ciò che si contiene nella Galleria del sig. Marchese Senatore Luigi Sampieri), or in any of the other known inventories, catalogues, and written descriptions of the Strada Maggiore palazzo that post-date Luigi Sampieri’s inheritance of the property. This includes the 1801 inventory of the quadreria compiled by Giovanni Tambroni, the keeper of the collection (fondo Talon Sampieri, A.219, fasc. 7), as well as Giacomo Gatti’s discussion of the collection in his Descrizione delle più rare cose di bologna, e suoi subborghi of 1803. The painting is also absent from the 1841 Catalogo dei quadri, ed altri oggetti d’arte esistenti nella Galleria Sampieri posta in Bologna Strada Maggiore, compiled after the majority of the Sampieri collection was sold by Francesco Sampieri, the son of Luigi, to the viceroy of the newly formed Kingdom of Italy Eugène de Beauharnais in 1811. The Saint Jerome was not among the works in the Sampieri collection sold to Eugène de Beauharnais, inventoried in the Stima delli sottonotati quadri esistenti nella famosa Galleria Sampieri di Bologna, dated 31 October 1810 (fondo Talon Sampieri, A.219, fasc. 7).

[xix] John Marciari has kindly shared his catalogue entry on the painting, written in preparation for the exhibition Italian Paintings from the Richard L. Feigen Collection in 2010, but never published as the painting was restituted prior to the exhibition—which is available upon request. Marciari dated the painting to the around 1588–1590 based on a comparison with several of Ludovico’s small-scale devotional pictures from this time.

[xx] Written communication, 8 July 2019; and Babette Bohn, Ludovico Carracci and the Art of Drawing, Turnhout, 2004, pp. 252–265, cat. nos. 121–131.

[xxi] Alessandro Brogi, “Il fregio dei Carracci con “Storie di Romolo e Remo” nel salone di palazzo Magnani,” in Il Credito Romagnolo fra storia, arte e tradizione, Bologna, 1985, p. 246; Alessandro Brogi, Ludovico Carracci (1555–1619), Bologna, 2001, vol. 1, pp. 271–273, cat. no. R51; and Alessandro Brogi, Ludovico Carracci: Addenda, Bologna, 2016, pp. 116, 118–120, footnotes 178, 184–185.

[xxii] For a discussion of Hermann Voss’s activities as a scholar and art collector, see: Kathrin Iselt, “Sonderbeauftragter des Führers”: der Kunsthistoriker und Museumsmann Hermann Voss (1884–1969), Cologne, 2010; and Camillo Miceli, Hermann Voss tra storia dell’arte e connoisseurship - carteggi e studi (1907–1966), PhD dissertation, Udine, 2009.

[xxiii] Katherin Iselt has shown that the narrative that Voss was dismissed from this post in Berlin for his liberal political views after the Nazis rose to power in 1933, commonly repeated in the literature and possibly originating with Voss himself, is false. See: Iselt, Sonderbeauftragter des Führers, p. 450; and Ilse von zur Mühlen, “Hermann Voss – Ein Kunsthistoriker im Dienste Adolf Hitlers,” AKMB-news, vol. 16, no. 2 (2010), p. 57.

[xxiv] Lee Sorensen, “Voss, Hermann.” Dictionary of Art Historians. http://www.arthistorians.info/vossh; and Gerhard Ewald, “Obituaries: Hermann Voss,” The Burlington Magazine, vol. 112, no. 809, British Art in the Eighteenth Century. Dedicated to Professor E. K. Waterhouse (August 1970), p. 541.

[xxv] The painting is listed in the catalogue as being from a “Privater deutscher Kunstbesitz.”

[xxvi] See the entry on the painting in the Lempertz catalogue “Die Bestände Der Galerie Stern Düsseldorf,” 13 November 1937, lot 181.

[xxvii] Iselt, Sonderbeauftragter des Führers, p. 436.

[xxviii] Research in the Nachlass Voss in the Deutsches Kunstarchiv in the Germanisches Nationalmuseum in Nuremberg, Voss’s photographic archive at the Nederlands Interuniversitair Kunsthistorisch Instituut in Florence, and elsewhere has not yielded any further clues to the earlier provenance of this work.

[xxix] The painting is now attributed to Franz von Riepenhausen. See: Iselt, Sonderbeauftragter des Führers, pp. 427 and 440.

[xxx] For a discussion of Leo Pauly’s role as agent for Hermann Voss, see: Iselt, Sonderbeauftragter des Führers, pp. 89–91.

[xxxi] Iselt, Sonderbeauftragter des Führers, p. 440. “Zu welchem Preis und wann genau Voss das Bild von Max Stern erwarb, ist nicht bekannt.”

[xxxii] For a full account of the forced closure of the Galerie Stern by the Nazi authorities, see: Catherine MacKenzie, ed., Auktion 392: Reclaiming the Galerie Stern, Düsseldorf, exh. cat., Montreal, Faculty of Fine Art Gallery, Concordia University, 20 October 2006–31 August 2008, pp. 13–14; and https://www.

concordia.ca/arts/max-stern/context.html.

[xxxiii] “Auflösung der Galerie Stern,” Internationale Sammler-Zeitung, no. 19 (1 December 1937), pp. 204–205; and Die Weltkunst, vol. 11, no. 46 (21 November 1937), p. 6.

[xxxiv] Prior to the 2000 sale, Lempertz responded to an inquiry from Richard Feigen regarding the provenance of the painting, stating: “We sold it [in] 1937 to a collector in the Rhine area.” See: Mattias Weller et. al, Kulturguterrecht - Reproduktionsfotografie - StreetPhotography Tagungsband des Elften Heidelberger Kunstrechtstags am 20. und 21. Oktober 2017, Baden-Baden, 2018, p. 43.

[xxxv] “Richard L. Feigen Returns Ludovico Carracci’s Depiction of St. Jerome He Unwittingly Bought,” Art Daily, 2009: http://artdaily.com/news/30696/Richard-L--Feigen-Returns-Ludovico-Carracci-s-Depiction-of-St--Jerome-He-Unwittingly-Bought-.

[xxxvi] John Marciari in Italian Paintings from the Richard L. Feigen Collection, New Haven, 2010, p. 130, footnote 5.