JOSÉ DE LA CRUZ

(Mexico,18th Century)

Virgin of Guadalupe

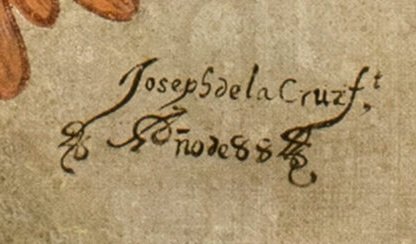

Signed and dated, lower right, Joseph de la Cruz f.t / Año de 88

Oil on canvas

81 x 54 inches (205.7 x 137.1 cm)

Provenance:

Private Collection, Santo Stefano d’Aveto (Genoa), ca. 1960-2019.

This monumental canvas is a rare, signed example of one of the most popular subjects of Spanish Colonial, and particularly Mexican, painting: the Virgin of Guadalupe. Paintings of the Virgin of Guadalupe record the 1531 vision of Juan Diego, a Chichimec peasant and Christian convert at Guadalupe, just outside of Mexico City. According to the legend, the Virgin Mary appeared as a young dark-skinned woman to Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin (his full name) and spoke to him in his native Nahuatl tongue. The cult of the Virgin of Guadalupe spread rapidly in the New World, particularly among the population of recently converted indigenous people. That the Virgin spoke in a local language and had dark skin was viewed as confirming the spiritual worthiness of indigenous Americans and underscoring the universality of Christianity. Today the Virgin of Guadalupe is venerated worldwide. Our painting is a rare signed and dated version by José de la Cruz, an artist active in Mexico in the late 18th century about whom little is known. José de la Cruz is known to have painted large-scale images of the Virgin of Guadalupe for export. Other examples by him are recorded in Seville and the Canary Islands; our painting in fact comes from the Ligurian town of Santo Stefano d’Aveto, Italy, which has long had a special devotion to the Virgin of Guadalupe.

According to the legend, in December 1531, shortly after the conquest of Mexico, Juan Diego heard a voice calling out his name while on his way to mass in a church outside Mexico City. A young dark-skinned woman appeared before him and told him that she was the mother of God and directed him to visit the bishop of Mexico, Juan de Zumárraga, to ask that a church be built in her honor on the hill of Tepeyac, the site of a former temple of the Aztec goddess Tonantzin. Juan Diego approached the bishop twice, but he required proof of this miraculous encounter. Juan Diego returned to the hill of Tepeyac and petitioned the Virgin for assistance. She reappeared and instructed him to pick the Castillian roses that were in full bloom on the hilltop (which had bloomed despite its being winter) and to return to the bishop. Juan Diego gathered the flowers in his tilmàtli—a type of native garment worn as a mantle. When Juan Diego returned to the bishop and opened his tilmàtli, he revealed the now universally recognizable standing figure of the Virgin imprinted on the fabric. This convinced the bishop of the miracle and led to the construction of a chapel on the site. The image of the Virgin that miraculously appeared on the tilmàtli, which still survives in a church on Tepeyac, served as the basis for all subsequent depictions of Virgin of Guadalupe.

The cult of the Virgin of Guadalupe became very popular among the indigenous population. Already by the mid-17th century the Virgin of Guadalupe was closely associated with Mexico and its people, and the image has remained culturally significant to the present day. In the year 1746, the Virgin was declared the patroness of the Viceroyalty of New Spain, and the image proliferated across Latin America, even making its way back to Europe as the cult of the became increasingly popular. Pope Benedict XIV approved the Office and Mass of the Virgin of Guadalupe in 1754, further cementing the legacy of the miracle and the image.

The present painting follows a standard type that stems from the original miraculous image. The Virgin appears at center on a half-moon supported by a winged putto. She stands with her proper left leg bent, as if stepping forward, and she looks downwards as she folds her hand in prayer. Her blue mantle is decorated with gold stars, and she is completely surrounded by a gold nimbus. She is surrounded by vignettes illustrating episodes from the legend of her appearance, and vines of soft-pink roses referencing those picked by Juan Diego trail up the outer edges of the painting, connecting the framed vignettes and the text corresponding to each image.

Although very little is known about José de la Cruz, it is possible to piece together some information about his career from the few documented paintings by him that have survived. In 1959, Joaquin Gonzalez Moreno recorded 5 paintings by José de la Cruz in Seville, each depicting the Virgin of Guadalupe on a large scale (measuring roughly 2 x 1 meters) and signed in a similar form to the present work.[1] Three of these examples are dated 1788, as is our painting, while the others are undated. More recently, Patricia Barea Azcón recorded another Virgen of Guadalupe by the artist in the Cathedral of La Laguna on Tenerife (Canary Islands), signed: “Joseph de la Cruz f[eci]t / Año de [17]89.”[2] The presence of a significant number of paintings by José de la Cruz in Seville and in the Canary Islands is a testament to the strong relationship between the Viceroyalty of New Spain and Spain itself during the Colonial period. The ports of the Canary Islands were used as a stopover point by the fleets traveling back and forth across the Atlantic. Those who ventured to New Spain evidently brought back paintings with them on their return to decorate their dwellings or donate them to religious institutions. It seems likely based on the surviving paintings by José de la Cruz that made their way to Europe, including the present painting, that the artist specialized in painting large-scale images of the Virgin of Guadalupe for export. It is no surprise that Seville, a port city from which many set sail for the New World, came to receive a significant number of paintings of the Virgin of Guadalupe by José de la Cruz. Nor is it surprising that the Virgin of Guadalupe found a significant cult following in Liguria, from which many sailors hailed.

[1] Joaquin Gonzalez Moreno, Iconografia Guadalupana, Mexico, 1959, pp. 74-75. These are in the Church of Santo Ángel Custodio, the Church of Santo Domingo in the city of Osuna (outside Seville), the Church of Saint Martin, the Convent of San Leandro, and in the private collection of José Luis Illanes del Río.

[2] Patricia Barea Azcón, “Pintura Guadalupana en las Islas Canarias,” Anuario de Estudios Atlánticos, no. 58 (2012), pp. 891-914. This painting was transferred to the Cathedral from the Ermita de Gracia in the same city.