BARTOLOMEO MANFREDI

(Ostiano 1582 – 1622 Rome)

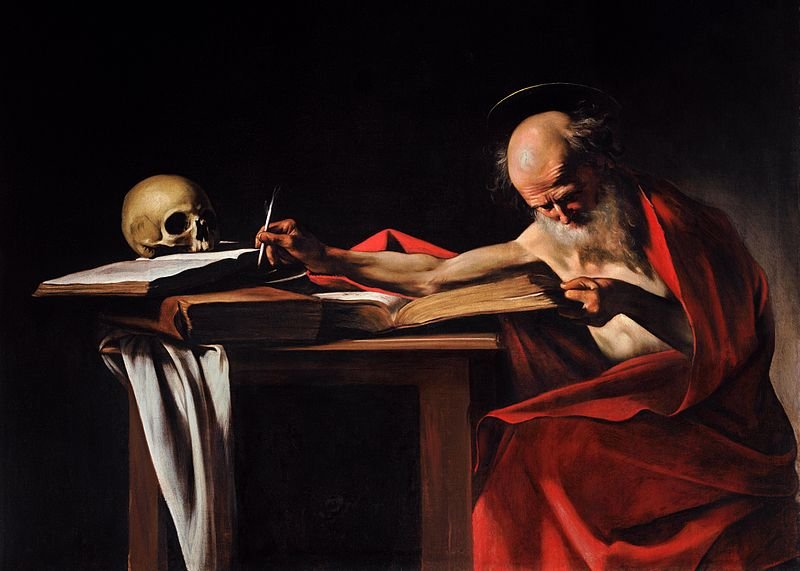

Saint Jerome Writing

Oil on canvas

50 ⅜ x 38 ⅜ inches (128 x 97.5 cm)

Provenance:

(Possibly) Cardinal Stefano Pignatelli, Rome

Giuseppe Pignatelli, Rome

Stefano Pignatelli, Rome, by 1647

Salvatore Romano, Florence

Private Collection, London

with Silvano Lodi, Milan, 2011

Private Collection, Italy

Literature:

Gianni Papi, “Per la fase giovanile di Manfredi: un nuovo San Gerolamo,” in Un Battito d’Ali: Ritrovamenti e Conferme, Milan, 2011, pp. 65-71.

Gianni Papi, Bartolomeo Manfredi, Soncino, 2014, p. 148.

Enrico Ghetti, “Un nuovo San Girolamo di Bartolomeo Manfredi,” in Paragone, vol. 145-146 (2019), p. 76.

Bartolomeo Manfredi was recognized as early as the seventeenth century as Caravaggio’s closest follower, yet his work never aped Caravaggio’s, but rather represented an evolution in both style and subject from it. It has been said, not without reason, that Manfredi invented Caravaggism, as so much of the work of the Caravaggisti is directly indebted to the “Manfrediana Methodus,” as it came to be called.

Despite Manfredi’s fame and the attendant collector interest through the nineteenth century, scholarship has only recently begun to separate his paintings from those of his contemporaries and imitators. Such problems are complicated by the almost total lack of documentation on the artist’s life, the absence of any signed paintings, and the sometime contradictory opinions of earlier critics. Although he may have arrived in Rome as early as 1603, Manfredi is not documented in the city until 1610, when he registered as living in the parish of Sant’Andrea della Fratte. The artist died in Rome in 1622 at the age of 40, but the evocative and engaging works that he painted during his short career had a profound influence in Rome and beyond.

The present work is one of Manfredi’s most powerful and effective compositions, depicting the figure of Saint Jerome seated at his desk with quill poised, dramatically turning from his work of translating the Bible into Latin. The saint’s mouth is slightly open, in wonderment and awe, as he receives inspiration from an unseen divine presence. The process of translation is demonstrably illustrated by the placement of a single leaf, only partially written upon, set within and over an open book presumably containing the Greek original. An inkwell rests at the table’s edge, while the vacant eye sockets of a skull, Jerome’s traditional emblem, seem to peer at the viewer from behind the drapery at the extreme left.

Manfredi’s points of departure in this monumental canvas are Caravaggio’s Saint Jerome of ca. 1605–1606 in the Galleria Borghese (Fig. 1) and his Saint Matthew and the Angel of 1602 in the Contarelli Chapel of San Luigi dei Francesi in Rome (Fig. 2)—both of which the artist would have known firsthand. As with Caravaggio’s Jerome, the depiction of the saint focuses on his role as translator of the Bible, but here recast into a vertical format that seems inspired by the Contarelli Saint Matthew. Manfredi’s composition is especially ambitious in its treatment of the mass of sweeping red drapery, which provides a kind of abstract reverberation of the motion and emotion of the figure. The drapery envelops both the saint and the table on which he writes—the corner of which seems to pierce the picture plane, projecting into the viewer’s space. Additionally, like Caravaggio’s Saint Matthew, our painting focuses on the moment of inspiration, the divine afflatus, which introduces an element of narrative into the composition.

Fig. 1. Caravaggio, Saint Jerome Writing, oil on canvas, 44 x 62 inches, Galleria Borghese, Rome.

Fig. 2. Caravaggio, Saint Matthew and the Angel, oil on canvas, 116 ½ x 74 ½ inches, San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome.

Dr. Gianni Papi has confirmed that our painting is not only the artist’s earliest treatment of the theme of Saint Jerome, but may indeed be one of Manfredi’s first major works, datable to 1610 or possibly even earlier.[i] The handling of the paint—particularly the confident brushstrokes that are clearly visible and appear freshly applied—indicate that this work was executed at an early stage in Manfredi’s development when he was in direct contact with Caravaggio. Papi also singles out the masterful handling of light—what he terms “the violence of the lights” (la violenza delle luci)—which brightly illuminates the saint and casts dark shadows across his face and shoulders.[ii]

The success and popularity of Manfredi’s composition is confirmed by the existence of a second version by the artist (Fig. 3), which postdates our painting by several years, as well as similar treatments of Saint John the Evangelist in his role as author of one of Gospels that were painted late in the artist’s career, ca. 1620–1622.[iii] The principal Saint John the Evangelist by Manfredi is that in the Pinacoteca Capitolina in Rome (Fig. 4)—additional versions are in the Pallavicini collection in Rome and formerly on the London art market. In light of the later versions it spawned, our Saint Jerome offers insight into the fascinating and complex fortuna of themes and types among the Caravaggesque painters and their patrons, exemplifying how a single, powerful composition such as the present one was absorbed, refashioned, and disseminated through the dynamics of that visual culture.

Fig. 3. Bartolomeo Manfredi, Saint Jerome, oil on canvas, private collection.

Fig. 4. Bartolomeo Manfredi, Saint John the Evangelist, oil on canvas, Pinacoteca Capitolina, Rome.

The early history of the painting is revealed by the presence of the coat-of-arms of the Pignatelli family on the reverse of the still unlined canvas. (An additional monogram, possibly “RN” has not yet been identified). The most important member of the family was Cardinal Stefano Pignatelli (1578–1623), a close friend of Cardinal Scipione Borghese, Caravaggio’s principal patron in Rome. Stefano Pignatelli was as well a patron of the arts and a collector, and likely commissioned our painting from the artist. An inventory of the collection of Giuseppe Pignatelli (probably Stefano’s brother or nephew) from 19 May 1647 confirms that our Saint Jerome was then in the possession of the family. It appears there as no. 180, “Un S. Girolamo, che scrive mezza figura grande del natural con cornice indorata del Manfredi.”

[i] Gianni Papi, “Per la fase giovanile di Manfredi: un nuovo San Gerolamo,” in Un Battito d’Ali: Ritrovamenti e Conferme, Milan, 2011, p. 68.

[ii] Papi, “Per la fase giovanile di Manfredi,” p. 67.

[iii] Papi, “Per la fase giovanile di Manfredi,” pp. 67, 71.