TOMASSO MINARDI

(Faenza 1787 – 1871 Rome)

Raphael’s Skull

Pencil on paper

9 ¾ x 14 ⅛ inches (24.6 x 36 cm)

Provenance:

Ettore Calzone Collection, Rome, by 1912.

Exhibited:

“Raffaello: L’Accademia di San Luca e il mito dell’Urbinate,” Accademia Nazionale di San Luca, Rome, 21 October 2020 – 31 January 2021, no. 25.

Literature:

Antonio Muñoz, “La Tomba di Raffaello nel Pantheon e la sua nuova sistemazione,” in Vita d’Arte, vol. 5, no. 53 (1912), pp. 172-173.

France Nerlich, “Raffaels heilige Reliquie Überlegungen zu einem kunsthistorischen Ereignis,” in Raffael als Paradigma. Rezeption, Imagination und Kult im 19. Jahrhundert, ed. G. Heiss, E. Agazzi, and E. Dècultot, Berlin, 2012, pp. 47-81, especially pp. 60-61, 389.

Anna Lisa Genovese, La tomba del divino Raffaello, Rome, 2015, pp. 103-105.

Stefania Ventra, in Raffaello: L’Accademia di San Luca e il mito dell’Urbinate, exh. cat., ed. Francesco Moschini, Valeria Rotili, and Stefania Ventra, Rome, 2020, cat. no. 25, pp. 149-153.

The recent celebratory exhibitions marking the 500th anniversary of Raphael’s death have brought renewed interest to an artist who has continuously captivated collectors, artists, and the public from his day forward. After his premature death, Raphael Sanzio was interred in the Pantheon in Rome at his request—making him the first artist to be accorded this honor. His epitaph hailed him as “the most eminent painter and rival of the ancients” and stated that “in his life great Mother Nature feared defeat and in his death she herself feared to die.”[i] By the 19th century, Raphael’s legendary status had risen to new heights, and his art remained a paradigm for Italian painters and all artists visiting Italy. Raphael’s influence is particularly felt in the works of Tommaso Minardi, author of the present drawing, who first arrived in Rome in 1803 from his native Faenza. Although he was in close contact with the painters Felice Giani and Vincenzo Camuccini early in his career, Minardi eventually rejected Neoclassicism and became one of the leading proponents of Purismo—an aesthetic movement that mirrored the tenets of the Pre-Raphaelites in Britain and the Nazarenes in Germany, emulating the style of earlier Italian artists. Minardi was one of the premier religious painters of his day in Rome, and his stylistic debt to Raphael is evident in many of his works (Fig. 1). After several years as the Director of the Accademia di Belle Arti in Perugia, which nurtured his interest in the great Renaissance artist, in 1822 Minardi was made Professor of Drawing of the Accademia di San Luca through the support of Antonio Canova and Pope Pius VII.

Fig. 1. Tommaso Minardi, Our Lady of the Rosary, 1840, oil on canvas, Galleria Nazionale D’Arte Moderna, Rome.

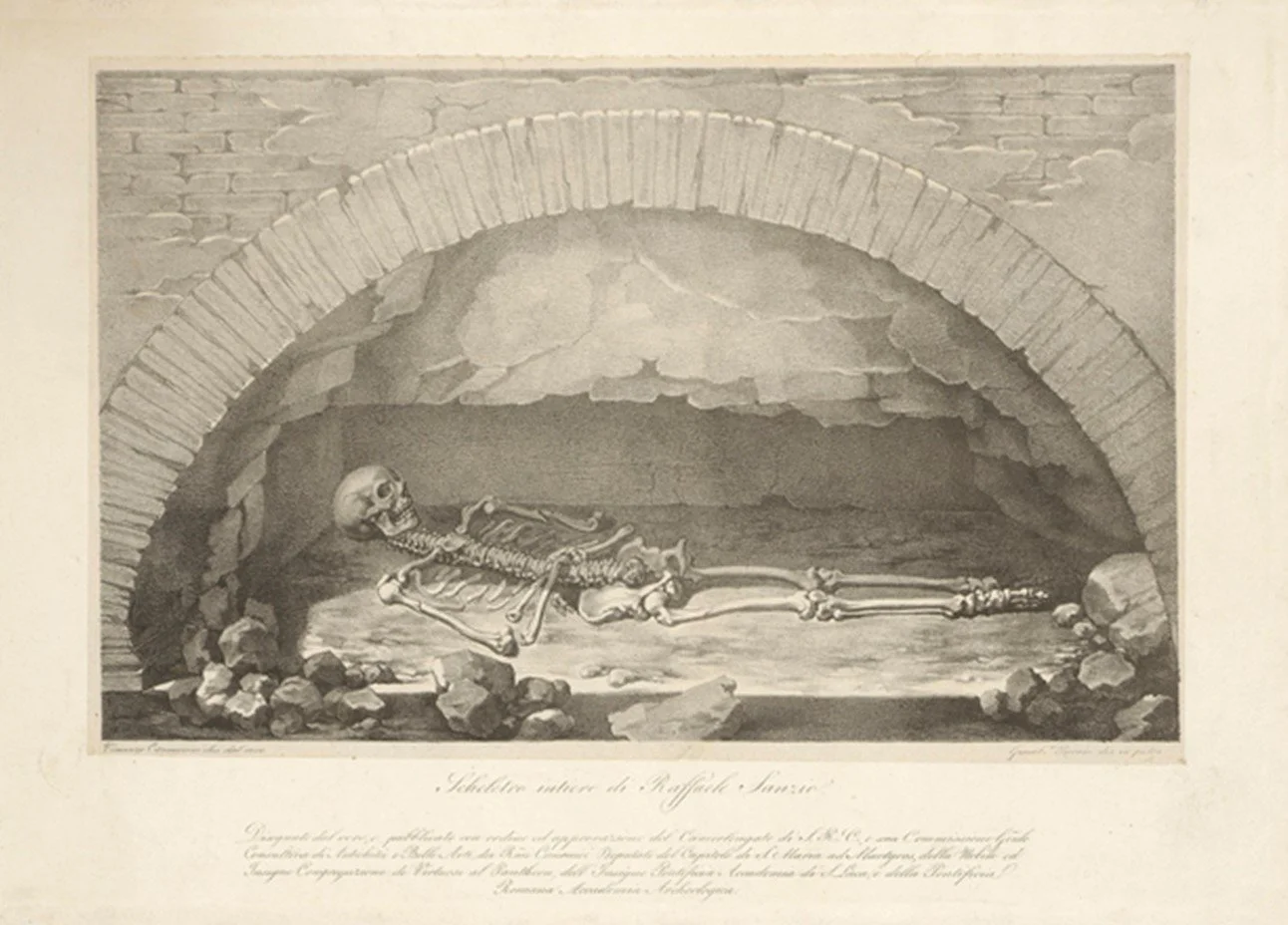

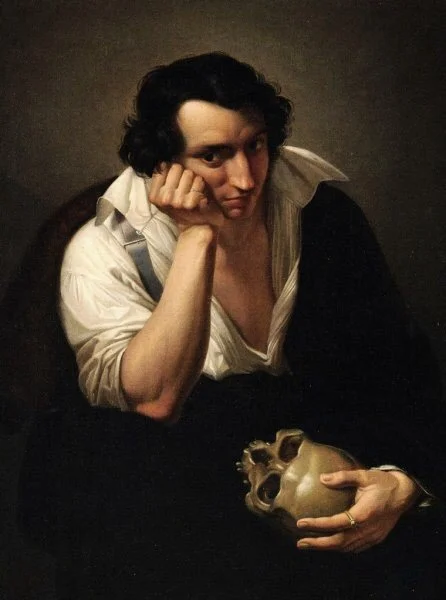

Minardi’s great skill as a draughtsman is evident in this meticulous rendering of Raphael’s skull, executed shortly after the artist’s body was removed from his tomb in the Pantheon (otherwise known as the Basilica of Saint Mary and the Martyrs). On 14 September 1833, Raphael’s sarcophagus beneath the altar of the Madonna del Sasso was opened on the orders of Pope Gregory XVI in order to confirm that the artist was truly buried there. The disinterring of Raphael’s body had been promoted by the Congregazione dei Virtuosi al Pantheon, the papal art academy of the arts, and the event was attended by the leading Roman figures and painters of the day, including Minardi who was a member of the Congregazione. Minardi was the first artist to propose making drawings of the artist’s remains, however, this task was initially entrusted to Vincenzo Cammucini, whose finished drawing was widely circulated as a lithograph (Fig. 2). Subsequently, Minardi was invited by the leader of the Congregazione, Giuseppe De Fabris, to carry out a graphic survey of Raphael’s skull and jaw, resulting in the drawing presented here, as well as a drawing of the detached mandible and a reconstruction of Raphael’s face.[ii] Interestingly, Minardi’s fascination with Raphael’s skull appears to have predated the artist’s disinterment. In 1827, Antonio Gualdi painted Minardi holding a skull in his hand (Fig. 3). This is most likely the skull that was famously kept in a display case at the Accademia di San Luca, which had traditionally been thought to belong to Raphael until the discovery of his remains and was treated as a relic by the students of the Accademia, who on the day of the festivities of San Luca would touch the skull with their pencils.[iii]

Our sheet was likely originally intended for the archive of the Congregazione dei Virtuosi al Pantheon, but Minardi ultimately retained the drawing in his possession. It later re-emerged in the collection of Ettore Calzone in Rome in 1912.

Fig. 2. G. B. Borani after Vincenzo Camuccini, The Skeleton of Raphael, lithograph, The Royal Collection, UK.

Fig. 3. Antonio Gualdi, Portrait of Tomasso Minardi with a Skull, 1827, oil on canvas.

[i] John Shearman, Raphael in Early Modern Sources 1483–1602, New Haven, CT and London, 2003, vol. 1, p. 640.

[ii] See: Antonio Muñoz, “La Tomba di Raffaello nel Pantheon e la sua nuova sistemazione,” in Vita d’Arte, vol. 5, no. 53 (1912), p. 173.

[iii] Stefania Ventra, in Raffaello: L’Accademia di San Luca e il mito dell’Urbinate, exh. cat., ed. Francesco Moschini, Valeria Rotili, and Stefania Ventra, Rome, 2020, cat. no. 25, pp. 149-150.