GIOVANNI FRANCESCO PENNI

(Italian, 1488?/96?-1528?)

Holy Family with Saint Catherine of Alexandria and the Young Saint John the Baptist

Oil on canvas, possibly transferred from panel

49 ¼ x 36 ⅞ inches

(125 x 93.5 cm)

Provenance:

Horatio Granville Murray-Stewart of Broughton, Cally House, Gatehouse-of-Fleet, Scotland (1834–1904), his armorial bookplate on the verso; probably sold at his estate sale, Robinson & Fisher, London, 12 May 1904[i]

Private Collection, Boston (there framed by Foster Brothers between 1906 and 1942)[ii]

with Childs Gallery, Boston, by 1955

Private Collection, Boston

Exhibited:

“El último Rafael,” Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid, 12 June–16 September 2012, no. 84.

“Raphaël les dernièrs années,” Musée du Louvre, Paris, 11 October 2012– 14 January 2013, no. 84.

“The meeting of two paintings. Gianfrancesco Penni, Holy Family - versions of Boston and Warsaw,” Muzeum Narodowego w Warszawie (National Museum in Warsaw), 4 February–31 March 2013.

Literature:

Tom Henry and Paul Joannides, Late Raphael, exh. cat., Madrid 2012; Spanish edition, El último Rafael, exh. cat., Madrid 2012; French edition, Raphaël les dernièrs années, exh. cat., Paris 2012; cat. no. 84, pp. 306-309, illustrated.

Sylvia Ferino-Pagden, “Review of Late Raphael Madrid and Paris,” The Burlington Magazine, vol. 154, no. 1361 (November 2012), p. 812.

David Love, “Gianfrancesco Penni: Designs for Overlooked Panel Paintings,” in Late Raphael: Proceedings of the International Symposium; Actas del Congreso Internacional, ed. Miguel Falomir, Madrid, 2013, pp. 139, 148, footnote 36.

Paul Joannides, “Afterthoughts on Late Raphael,” in Late Raphael: Proceedings of the International Symposium; Actas del Congreso Internacional, ed. Miguel Falomir, Madrid, 2013, p. 170.

Grażyna Bastek, Barbara Łydżba-Kopczyńska, Elżbieta Pilecka-Pietrusińska, and Iwona Maria Stefańska, “Technological Examination of the Warsaw and Boston Versions of The Holy Family with Saint John and Saint Catherine by Gianfrancesco Penni,” Journal of the National Museum in Warsaw, New Series, vol. 3, no. 39 (2014), pp. 181-195; in Polish as “Święta Rodzina ze świętym Janem Chrzcicielem i świętą Katarzyną Aleksandryjską Gianfrancesca Penniego — badania technologiczne wersji,” Rocznik Muzeum Narodowego w Warszawie, Nowa Seria, vol. 3, no. 39 (2014), pp. 151-180.

David Love, “Gianfrancesco Penni: A Biographical and Iconographic Introduction to His Two Versions of The Holy Family with Saint John and Saint Catherine,” Journal of the National Museum in Warsaw, New Series, vol. 3, no. 39 (2014), pp 217-231; in Polish as “Gianfrancesco Penni — wprowadzenie biograficzno – ikonofgraficzne do jego dwóch wersji Świętej Rodziny ze świętym Janem Chrzcicielem i świętą Katarzyną Aleksandryjską,” Rocznik Muzeum Narodowego w Warszawie, Nowa Seria, vol. 3, no. 39 (2014), pp. 196-216.

Paul Joannides, “Gianfrancesco Penni’s Two Versions of The Holy Family with Saint John and Saint Catherine,” Journal of the National Museum in Warsaw, New Series, vol. 3, no. 39 (2014), pp. 245-254; in Polish as “Dwie wersje obrazu Święta Rodzina ze świętym Janem Chrzcicielem i świętą Katarzyną Aleksandryjską Gianfrancesca Pennigo,” Rocznik Muzeum Narodowego w Warszawie, Nowa Seria, vol. 3, no. 39 (2014), pp. 232-244.

David Love, “The Currency of Connoisseurs: The History of Two Versions of The Holy Family with Saint John and Saint Catherine by Gianfrancesco Penni,” Journal of the National Museum in Warsaw,New Series, vol. 3, no. 39 (2014), p. 285; in Polish as “Waluta koneserów — o historii dwóch wersji Świętej Rodziny ze świętym Janem Chrzcicielem i świętą Katarzyną AleksandryjskąGianfrancesca Penniego,” Rocznik Muzeum Narodowego w Warszawie, Nowa Seria, vol. 3, no. 39 (2014), pp. 272-273.

The recent “Late Raphael” exhibition, shown at the Louvre and the Prado in 2012–2013, not only illuminated the career of Raphael in his last decade, but gave order to the life and works of Giovanni Francesco Penni, Raphael’s principal assistant and closest follower. A previously unpublished painting first presented in the exhibition was the present work, Penni’s Holy Family with Saint Catherine of Alexandria and the Young Saint John the Baptist, which had long remained unidentified in a private Boston collection, there familiarly referred to as “the old Italian painting.” Its reemergence is a notable addition to our knowledge of the High Renaissance and, in particular, of Roman classicism in the circle of Raphael.

Giovanni Francesco Penni and Giulio Romano were the joint heirs, both practically and artistically, of Raphael’s studio following the master’s death in 1520. They worked together in the first years of the decade, collaborating most famously on the frescoes of the Sala di Costantino in the Vatican Palace and the Monteluce Coronation, now in the Vatican Pinacoteca. But after the Sack of Rome in 1527 their careers dramatically diverged. Giulio moved to Mantua where he was to enjoy the patronage of the Gonzaga family until his death in 1546. Penni’s life after Rome was shockingly brief. He joined the retinue of the Marquis Alfonso d’Avalos and traveled with him to Ischia and Naples before dying of unknown causes in 1528.

Penni’s early work is essentially Raphael’s. He participated in most every major project of Raphael’s from 1513 on while organizing the practical workings of the studio, thus acquiring his nickname “il Fattore,” or “the Manager.” Although aspects of his personal style are perceptible in many of the productions of the Raphael workshop, tellingly no documented independent paintings by Penni are known from Raphael’s lifetime. Nonetheless his elegant refined style is discernable in several paintings from the second decade of the century—many of which have until recently been given to Raphael himself. While Giulio Romano is the more distinctive and inventive of the two, Penni was clearly the more faithful in executing and later carrying forth the aesthetics of his master.

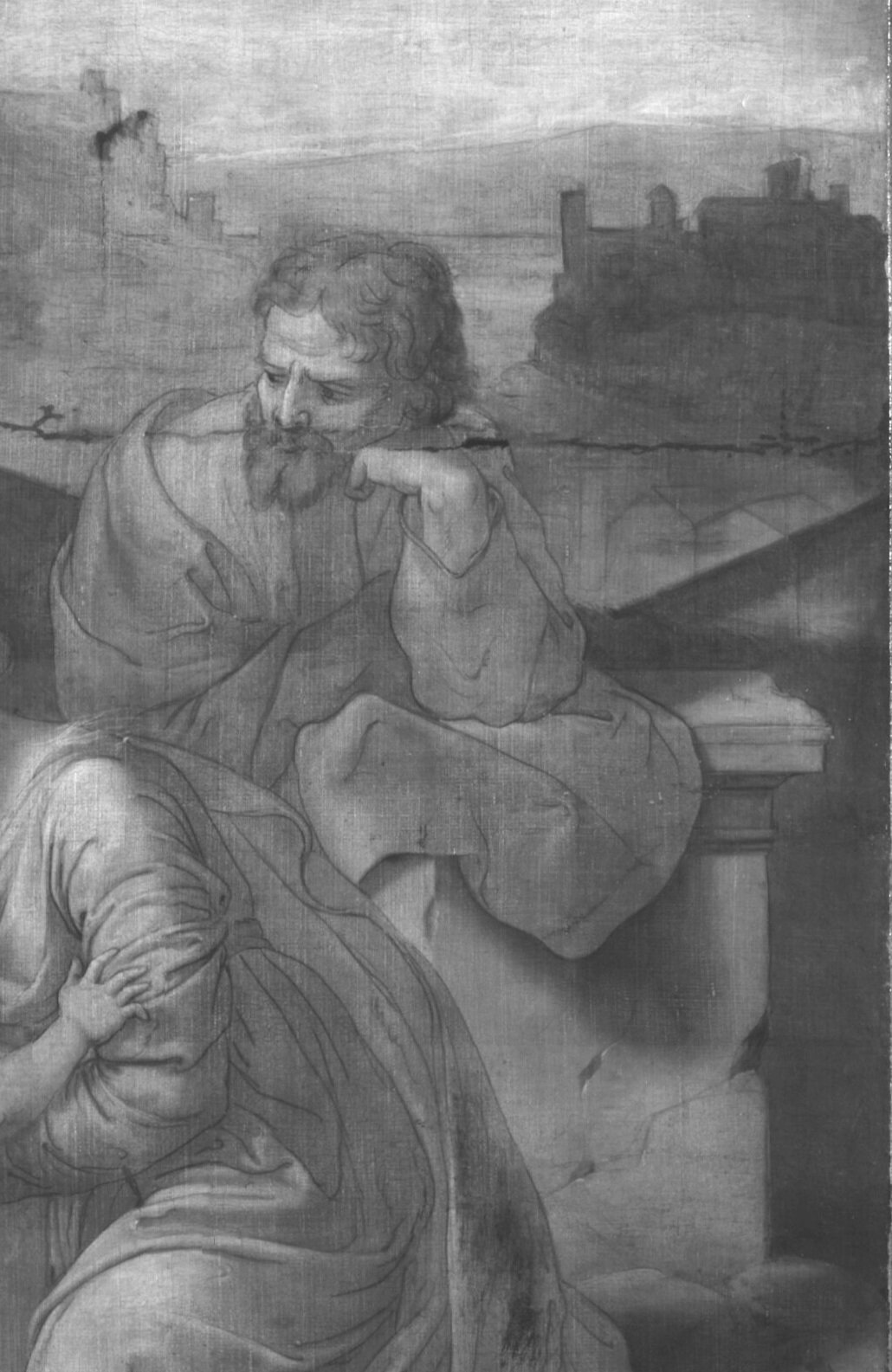

The Holy Family with Saint Catherine of Alexandria and the Young Saint John the Baptist was first attributed to Penni in 2004 by Paul Joannides,[iii] who noted that it was a variant of a known composition by the artist in the collection of the National Museum of Warsaw (Fig. 1).[iv] Since then both paintings have been extensively studied, separately and together, by scholars and conservators employing advanced technical imaging and analysis. The present painting was exhibited in the “Late Raphael” exhibition, but due to legal issues the Warsaw panel could not be included. However, in 2013 the two paintings were shown together in a focus exhibition in Warsaw and discussed in a conference convened on 4 February 2013. The conclusions of that conference are related in the 2014 publications cited above. These confirmed that both versions of the composition are autograph and that they were executed side-by-side in the same studio. Technical images of the paintings demonstrated that the principal figures were prepared using the same cartoon. Infrared reflectography also revealed identical compositional changes in the underdrawing—a group of buildings were planned to the right of Saint Joseph in both works, but were not painted (Fig. 2).[v] Although it was impossible to determine the primacy of either version, the many variations between the two paintings—most notably in the landscape treatment and palette but also in details such as Saint Catherine’s hair-style, tiara, and her fastened or unfastened sandal—reveal the creative process involved in the gestation of these two related compositions.

Fig. 1. Giovanni Francesco Penni, Holy Family with Saint Catherine of Alexandria and the Young Saint John the Baptist, Warsaw, National Museum.

Fig. 2. Infrared reflectography of the present painting.

The setting of our Holy Family is a broad landscape with classical ruins perched on a rocky outcropping. In the distance a river dotted with small ships wends its way into the distance between villages on either bank. In the foreground the Christ Child emerges from his cradle to embrace his mother as Joseph sternly observes from his post leaning against a damaged stone pedestal, a further emblem of the old order supplanted by Christianity. Catherine stands to the side, her right hand gently grasping the arm of the young John the Baptist, her left hand poised atop her wheel. While the three principal figures of the composition are directly drawn from Raphael’s Holy Family of Francis I in the Louvre (Fig. 3), the two saints at the left are Penni’s inventions. The figure of Saint Catherine—in pose, dress, and detail—is derived from classical models, particularly a Roman figure of Minerva, and can be associated with antiquities recorded in the so-called Fossombrone Sketchbook, the work of an unidentified draughtsman in Raphael’s circle. Similarly, the evocative Roman ruins above her head, which depict the Baths of Caracalla, clearly relate to drawings in the same source (Fig. 4).[vi]

Fig. 3. Raphael Sanzio, The Holy Family of Francis I, Paris, Louvre.

Fig. 4. Detail of the present work.

Our painting and its Polish cognate have been extensively studied in the publications cited above. There David Love treats the intricate and involved iconography of the composition, the fusion of classical and modern imagery, the significance of the scene depicted—which exists out of time, Catherine having lived in the fourth century—and its religious import and connection with evangelical theology. Both Love and Joannides discuss the relationship of the two versions, the placement of the painting within Penni’s career, and possible issues of patronage. They date the painting, as does Tom Henry, soon after Raphael’s death, contemporary with the Monteluce Coronation, ca. 1521–1522.[vii]

Grażyna Bastek and her colleagues study and review the technical issues involved in both paintings’ facture and conservation, incorporating their own findings on the Warsaw painting with the results of the technical examination undertaken in 2011 by Kate Smith of the Straus Center for Conservation at Harvard. However, subsequent to these reports, the present painting was cleaned in 2014 by Anthony Moore, a dramatically successful treatment that removed passages of repaint and discolored varnish which had compromised the painting’s appearance during its exhibition in Paris, Madrid, and Warsaw. One question, still unresolved, is that of the picture’s original support. While Bastek believes that the painting was transferred from panel to canvas sometime in the nineteenth century, Moore contends that it remains on its original canvas support. In any case, the paint surface is remarkably intact with only minor localized losses.

[i] No catalogue for this sale has been so far located, but an advertisement in The Times of London on 11 May 1904, p. 16, notes “Willis’s Rooms, King Street, St. James’s Square. On View – A Collection of Pictures and Drawings, chiefly of the Modern School, the property of a Lady; Pictures of the Dutch and Italian School, by direction of the Executors of the late Horatio Granville Murray-Stewart, removed from Cally, Gatehouse, N.B., and from other sources. Messrs. Robinson and Fisher are instructed to sell at their Rooms, as above, To-morrow (Thursday) May 12th, at 1 o’clock precisely, a collection of Pictures and Drawings, as above, comprising examples by [several artists none relevant] May be viewed, and catalogues had.” Murray-Stewart’s collection was clearly significant. The collector and dealer Herbert Horne attended this sale and purchased Bernardo Daddi’s Coronation of the Virgin, now in the National Gallery, London, and Giotto’s Saint Stephen, now in the Museo Horne, Florence. He also noted a Botticelli school Virgin and Child with Two Angels, but it is unclear whether he acquired it. Charles Ricketts refers to the auction in his diary (British Library Add Ms 58116, 27r, as noted by Caroline Elam). At the sale Ricketts and Charles Haslewood Shannon evidently acquired an anonymous Florentine Virgin and Child, a work later given to the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, as by Bicci di Lorenzo. Other paintings known to have been owned by Murray-Stewart (so identified, as with the present work, by the placement of his armorial bookplate on the verso, include Magnasco’s Landscape with Figures in the Seattle Museum of Art (inv. no. 57.58) and the Argolla Players by Pedro Núñez de Villavicencio, sold at Sotheby’s, London, 4 December 2013, lot 15. See: Simona Di Nepi, Ashok Roy, and Rachel Billinge, “Bernardo Daddi’s Coronation of the Virgin: The Reunion of Two Long-Separated Panels,” National Gallery Technical Bulletin, volume 28 (2007), p. 6 and 23, footnotes 15 and 16; Herbert P. Horne, Alessandro Filipepi, commonly called Sandro Botticelli, Painter of Florence. Appendix III: Catalogue of the Works of Sandro Botticelli, and of his disciples and imitators, together with notices of those erroneously attributed to him, in the public and private collections of Europe and America, ed. Caterina Caneva, Florence, 1987, p. 60; Elisabetta Nardinocchi, Museo Horne: Guida alla Visita del Museo, Florence, 2011, p. 85; J. W. Goodison and G. H. Robertson, Fitzwilliam Museum Cambridge: Catalogue of Paintings, Cambridge, 1967, vol. 2, pp. 54–55, cat. no. 1987; and Malcolm McLachlan Harper, Rambles in Galloway, Edinburgh, 1876, p. 85, which briefly mentions the artistic holdings of Cally House: “In the drawing-room, among a variety of other pictures, are specimens of Claude Lorraine and Poussin, etc., and in the other rooms Velasquez, Ruysdael, Wouvermans, Murillo, Durer, Reynolds and other famous masters are represented.”

[ii] A label on the painting’s verso is marked “Foster Brothers/ 4 Park Sq./ Boston/ Picture Frames/ order # 2363” and another bears the number “C-378.” Foster Brothers moved from 3 Park Square to 4 Park Square between 1902 and 1906. They continued at 4 Park Square until they ceased business in 1942.

[iii] Joannides notes that the painting was first associated with Penni by Eliza Katz Ward. See: Paul Joannides, “Afterthoughts on Late Raphael,” in Late Raphael: Proceedings of the International Symposium; Actas del Congreso Internacional, ed. Miguel Falomir, Madrid, 2013, p. 170.

[iv] The Warsaw painting has an illustrious provenance: Vincenzo I Gonzaga, Mantua; Charles I of England; his gift to the Duke of Hamilton Grand Duke Leopold Wilhelm; Pope Clemente XIV; Count Kaunitz, Vienna; Count Potocki, Cracow, and by descent until acquired by National Museum, Warsaw in 1949. For a discussion of this, see: David Love, “The Currency of Connoisseurs: The History of Two Versions of The Holy Family with Saint John and Saint Catherine by Gianfrancesco Penni,” Journal of the National Museum in Warsaw, New Series, vol. 3, no. 39 (2014), pp. 274–284.

[v] Grażyna Bastek, Barbara Łydżba-Kopczyńska, Elżbieta Pilecka-Pietrusińska, and Iwona Maria Stefańska, “Technological Examination of the Warsaw and Boston Versions of The Holy Family with Saint John and Saint Catherine by Gianfrancesco Penni,” Journal of the National Museum in Warsaw, New Series, vol. 3, no. 39 (2014), pp. 182–183; and Paul Joannides, “Gianfrancesco Penni’s Two Versions of The Holy Family with Saint John and Saint Catherine,” Journal of the National Museum in Warsaw, New Series, vol. 3, no. 39 (2014), p. 253.

[vi] Joannides, “Gianfrancesco Penni’s Two Versions,” pp. 252–253. The drawings referred to here are found on foglios 10 verso, 83 recto, and 84 recto of the Fossombrone Sketchbook. See: Arnold Nesselrath, Das Fossombrone Skizzenbuch, London, 1993, plates 18, 64, and 65.

[vii] Joannides, “Gianfrancesco Penni’s Two Versions,” pp. 249–250; Bastek et. al, “Technological Examination,” p. 182.