SPANISH SCHOOL, late 18th Century

Saint Benedict of Palermo

Polychrome wood

29 ½ x 15 x 12 inches

Base: 5 ⅞ x 15 ¼ x 16 ¾ inches

Overall height: 34 ⅜ inches

Provenance:

Private Collection, Spain.

This impressive polychrome sculpture depicts Saint Benedict of Palermo (ca. 1524–1589), the first Black saint canonized in modern times. Saint Benedict is known by several names, reflecting the cultural prejudices of his times and the extent of the posthumous veneration dedicated to him. He was born Benedetto Manasseri in a village near Messina once called San Filadelfo and now San Fratello—hence his sobriquets, Benedetto da San Filadelfo and Benedetto da Sanfratello. His parents, Christoforo and Diana, were Christians of Ethiopian origin. Christoforo was enslaved by a certain Vincenzo Manasseri; Diana, manumitted according to some sources, had the surname of her “padrone” Larcan. It is uncertain whether Benedict was born free or was freed at the age of ten, but his skin color engendered the more familiar names by which he is known: Benedetto (or Benito in Spanish) Moro (Benedict the Moor), Benedict the African, or Benedict the Black.

We know that he received no formal education and was working as a farm hand when, at the age of twenty-one, he met Girolamo Lanza, an itinerant noble ascetic, who had formed a group of devout hermits which Benedict soon joined. He remained with them until 1562, when Pius IV ordered the dissolution of their hermitage and their transfer to established monastic orders. Benedict then joined the Franciscans, becoming a lay brother at the Monastery of Santa Maria di Gesù near Palermo. His duties there were modest ones, preparing food in the kitchen and sweeping the monastery floors, but his humility, piety, and asceticism were recognized, and he was eventually appointed Guardian and Master of the Novices at the Monastery—extraordinary positions in light of his evident illiteracy. Early accounts attest to his devotion to a life of poverty and obedience, to austerity, self-mortification and charity—which led to tales not alone of good works, but miracles: occurrences of the materialization of food and wine (such as, the replication of loaves of bread and the appearance of ripe oranges in winter) and extraordinary demonstrations of prophecy, reanimation, and cures of blindness, dire illnesses, and myriad afflictions.

Benedict’s path to sainthood began soon after his death in 1589 and continued over the next two centuries. While popular veneration of Benedict was considerable (though unsanctioned), the official process of canonization proceeded slowly. It began in 1595, following the mandatory five-year hiatus after his death when an “ordinary process” was initiated. Two apostolic inquiries followed in 1620, another two in 1625. In 1716 a process was held at the Church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva in Rome, focusing on the cult devoted to Benedict, which by then had proliferated across Iberia to the Spanish and Portuguese colonies of the New World—especially Peru, Mexico, and Brazil. Benedict was finally beatified in 1743 but canonized only in 1807.

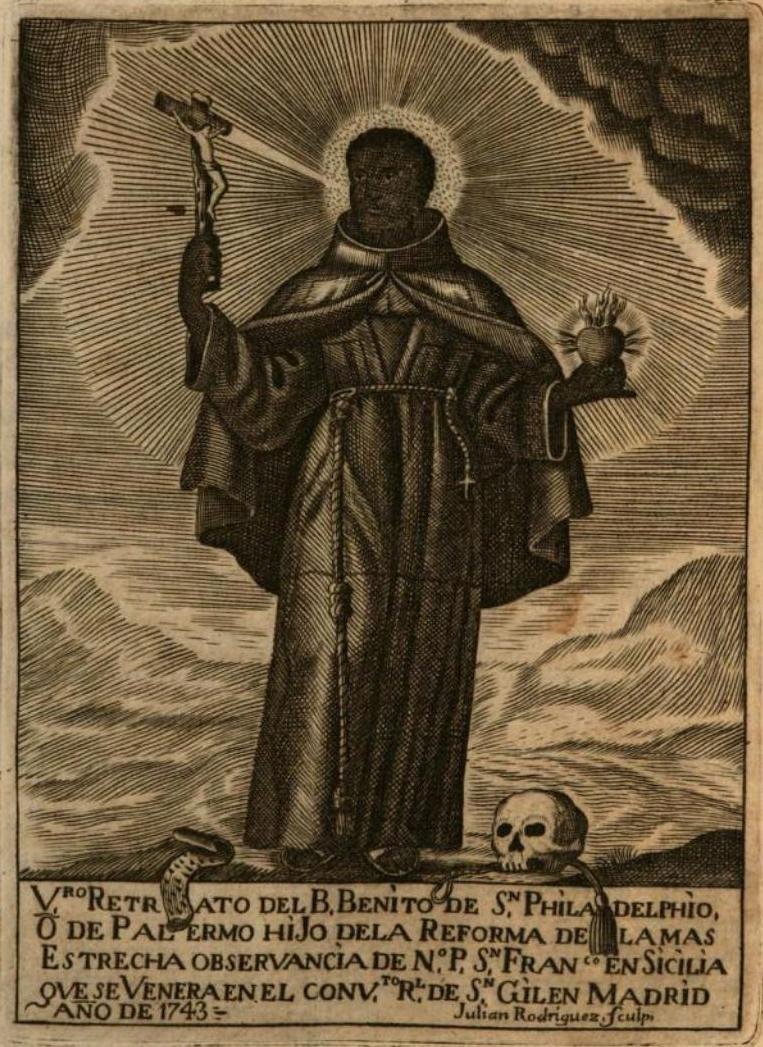

Our sculpture of Saint Benedict derives from an iconographic type that was current in the 17th and 18th centuries in Spain, following a prototype that was at one time venerated in the Franciscan Monastery of San Gil in Madrid. Although that polychrome sculpture was destroyed during the French invasion of Spain in the Napoleonic era, it is recorded in a 1743 engraving by Julián Rodriguez which appeared in Antonio Vicente de Madrid’s Life of the saint titled El negro más prodigioso (Fig. 1).[i] As in the engraving, our sculpture depicts Benedict in a finely striped Franciscan habit edged with gold and belted by a gilt cord. He holds aloft a crucifix while grasping a flaming heart banded with thorns and surmounted by a diminutive cross. The heart symbolically alludes to the ecstatic event described by Benedict’s hagiographers—at his death his flaming heart (“encendido corazón”) burst from his chest to be united with Christ.[ii] As in nearly all depictions of Benedict he is shown at a youthful age with a dark complexion devoid of shading, standing in a relatively static pose, but with an intense gaze, here enlivened by the sculptor’s use of glass eyes.

Fig. 1. Julián Rodríguez, Saint Benedict of Palermo, engraving.

Benedict’s cause for sainthood was supported and amplified by the Church and the Spanish Monarchy. Erin Kathleen Rowe has written: “Habsburg monarchs had begun an ambitious project of elevating holy people from all regions of its composite monarchy, including Rose of Lima, Isabel of Portugal, and John of God. Philip [that is, Philip III] had two levels of interest in Benedict’s cult – first it highlighted the sanctity of Sicily, one of his dominions, and second, it offered help in the long effort of evangelizing to existing and new populations of enslaved Africans throughout the empire.”[iii] Parallel with these efforts were the establishment of black confraternities, first in Spain and Portugal, but soon in Spanish America. Rowe writes: “The tradition of black confraternities had been firmly in place for over a century before the entrance of Benedict’s cult to the Iberian Atlantic, yet black saints and black confraternities quickly became intertwined. In fact, black confraternities became the primary vehicle through which devotion to black saints spread. Black saints, then, emerged out of the brutality of early modern slavery and the attendant collision of Africans and Christianity.”[iv]

Devotion to Benedict was shared by all races, but his appeal to Black people, whether enslaved or free, was special. He was the first Black figure to be beatified and canonized in modern times and from the broad devotion that emerged, he has become the Patron Saint of African Americans, African missions, enslaved people, as well as co-patron (with Saint Rosalia) of the city of Palermo. Today he remains one of the most deeply venerated saints throughout the New World. In Venezuela a series of festivals and processions dedicated to Benedict take place every winter. These incorporate African, European, and indigenous traditions, featuring elaborate costumes, vibrant dances, and drum orchestras of African origin known as chimbanguéles.

[i] Antonio Vicente de Madrid, El Negro más prodigioso. Vida portentosa del beato Benito de S. Philadelphio o da Palermo, llamado comunmente el Santo Negro, etc., Madrid, 1744.

[ii] Rowe, Black Saints, p. 152, citing Francisco Antonio Castellano, Compendio de la vida…, Murcia, 1752, p. 78.

[iii] Erin Kathleen Rowe, Black Saints in Early Modern Global Catholicism, Cambridge, 2019, p. 42, referencing Bernard Vincent, “Saint Benôit de Palerme et l’Espagne,” in Schiavitù, religione e libertànel Mediterraneo tra Medioevo ed età moderna, ed. Giovanna Fiume, Cosenza, 2008), pp. 201-204.

[iv] Rowe, Black Saints, p. 47.